The Liquid Society

Mark Lilla

1.The 2016 election

For four years now American political scientists and journalists have been trying to explain the outcome of the 2016 presidential election and draw lessons for the future. There are interpretations available to suit every taste. Some stress the rise of populism (however defined), others the polarizing role of the internet (aided, for some, by Russian interference), the dominance of identity politics in the Democratic Party, the transformation of conservative media outlets into far-right propaganda agencies, large-scale immigration, racism against migrants and minorities, and so on. The American public is familiar with all these interpretations by now and none seems particularly fresh or surprising.

*

The one exception is a remarkable study conducted by the bipartisan Democracy Fund Voter Survey Group, whose report was drawn up by Lee Drutman of the liberal New America Foundation in Washington. Published in the summer of 2017 under the title Political Divisions in 2016 and Beyond: Tensions Between and Within the Two Parties it remains the most thought provoking of all the many analyses that have been issued over the past four years.1

*

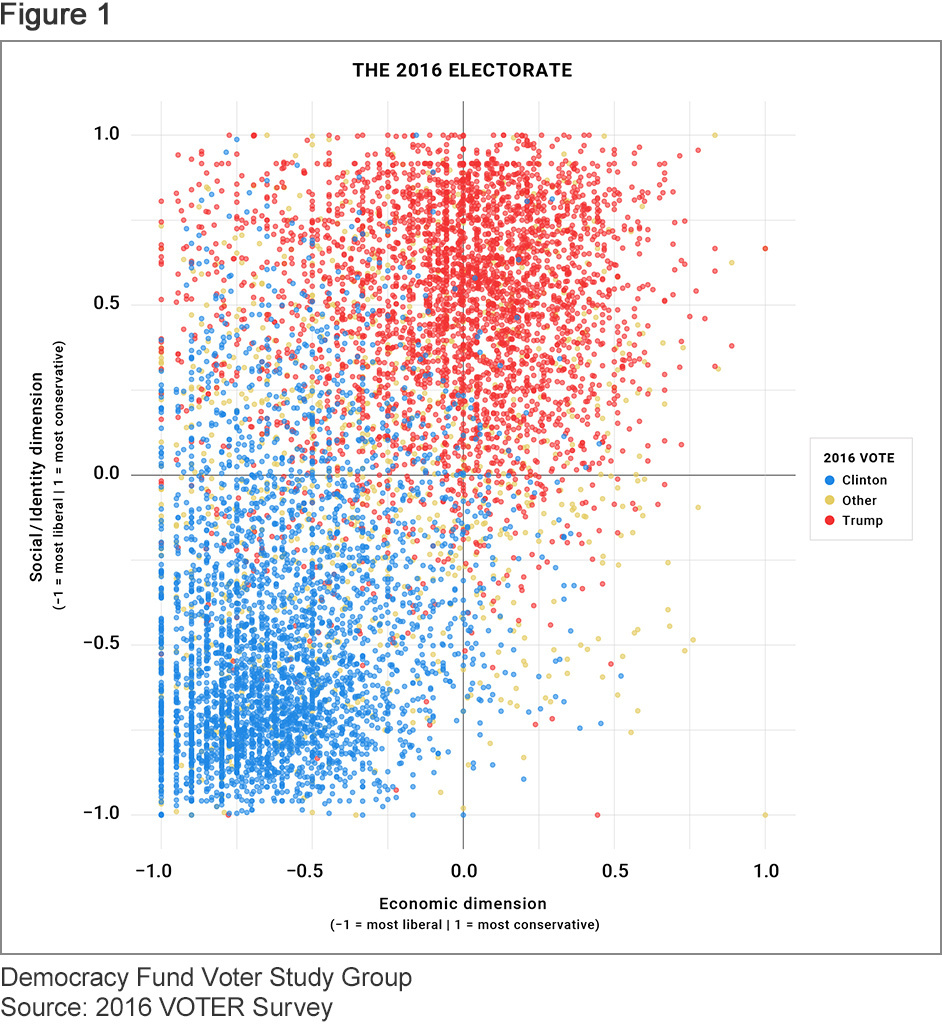

What sets this report apart is that researchers understood that the Trump phenomenon did not fit easily into the familiar dichotomies usually invoked when trying to understand the basic cleavages in American political life today. Right v. left, populist v. mainstream, red states v. blue states, “somewheres” v. “anywheres,”2 “pickup” people v. Prius people.3 All these cleavages exist but don’t fully explain America’s new political cultures and the complex motives that led to the election of Trump. The Group’s approach was to distinguish two broad sets of issues – economic and “social-identity” ones – and then to compare Trump and Hilary Clinton voters along these two dimensions simultaneously. They created an economic index based on voters’ views on economic inequality, basic health and retirement programs, trade, government intervention in the economy, and whether economic conditions were improving for people like them. They then compiled a social-identity index to reflect voters’ views regarding gender equality, race, immigration, Islam, gender, gay marriage, and abortion.

*

The most striking and surprising result of the study is that there is now far less disagreement among American voters on economic issues than on social/identity ones. This was not the case during the Reagan and Bush years, when views on both sets of issues were highly polarized. Today the country as a whole, including traditional Republican voters, has moved left on issues like trade and the need for a basic social safety net, especially health care. Conservatives and liberals still differ significantly, but the median voter is now liberal on questions of inequality. On restricting foreign trade, Trump voters were even further to the left than liberal Clinton voters were. (Paradoxically, though, Trump voters were generally hostile to government intervention to address these problems, while Clinton voters were favorable.) The widest gaps between the two sets of voters concerned “social-identity” issues, in particular immigration and “morality” (sexuality, abortion, marriage).

The significance of these results can best be appreciated visually in a striking scatterplot in the Group’s report (Fig. 1). The horizontal axis plots economic views, from liberal to conservative as the eye moves right. The vertical axis plots social-identity views, from liberal to conservative as the eye moves down. This creates fours quadrants, representing four possible political positions.

*

In a symmetrical, simple world one would expect the upper-right quadrant to be thick with red dots, representing Republicans who were conservative on both economics and society-identity issues, and the lower-left quadrant to be thick with blue dots, representing Democrats who were liberal on both sets of issues. This is no longer the case, if it ever was. Instead one notices three things today:

- • the Republican base has moved left on economic issues

- • the Democratic base has moved even further left on social/identity issues

- • a substantial fraction of voters (nearly 30%) now hold liberal views on the economy but more conservative ones on society-identity.

*

The Survey Group calls this last group of voters “populists.” For the purposes of their study this makes perfect sense, since the Group was trying to explain how a populist like Donald Trump was elected. And what they discovered is that a decisive portion of Obama voters who are economically liberal but socially conservative switched to Trump in 2016. And that was enough to defeat Hilary Clinton.

*

The implications of these findings are much larger, however. They seem to confirm the dissolution of the electoral bases of both the Democratic and Republican parties continues apace and that a significant portion of the electorate does not recognize itself fully in either party as currently constituted. For some time now “independent voters,” who shift from party to party depending on circumstances and the candidates on offer, have been a significant force. Up until now, though, we have assumed that this group was somewhat inconsistent in its preferences and that what mainly held it together was cynicism about politics, which led it to vote against rather than for candidates. Or to vote for candidates who themselves express cynicism about the American political system. This is what has made them susceptible to populism – which is certainly to some extent true.

*

But the Study’s Group research also allows us to pose a different question, which is whether there is some deeper and more consistent ideological outlook that that unites these voters. Using the Group’s definitions, their outlook seems incoherent because it is liberal on some issues and conservative on others. But what if we drop the terms “liberal” and “conservative” and simply pay attention to the issues that matter to these voters, and then ask ourselves whether their positions bear a shared family resemblance. Is there at some level a rational, or at least psychologically compelling, connection between being opposed to tariff-free trade and immigration? Or between thinking that the economy does not help “people like me” and that gay marriage is wrong? Stated in these terms, one can already see a possible affinity among these positions: a distrust of change. I think there are good reasons to believe that this distrust – call it fear, anxiety, or uncertainty – has become one of the major forces in modern politics, not just in the United States but in many other countries. What we are beginning to see is an increasingly coherent response – and not just a mindless reaction – to what might be called the advancing “liquidity” of all modern societies.

*

2.The liquid society

The term “liquidity” became central to sociological theory in recent decades thanks to the work of Zygmunt Bauman, a Polish scholar who was for many years at the London School of Economics before his death in 2017. Bauman wrote on many subjects, but in the early 2000s began concentrating on what he called “liquid modernity.” The term “liquid” is an oblique reference to the Communist Manifesto where Marx and Engels declared that under capitalism, “all that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.” The implication of this observation, Bauman pointed out, is that solidity is a good thing and that once unstable capitalist society was overthrown, a new, solid type of society under communism would emerge. The whole point of engaging in socialist and communist politics was to achieve solidity and certainty a means to social justice – hence the importance of values like solidarity and policies like economic planning.

*

The communist utopian dream is dead and capitalism remains in place – indeed it has entered an even more destabilizing phase, according to Bauman. Capitalism no longer just destroys solid social institutions, it prevents new solid one from even forming. We now live in a “liquid modernity” in which people have begun to anticipate that none of our institutions or norms will endure very long. Instead, we will all be living in a state of radical uncertainty. At the same time that institutional lifespans are decreasing, the human lifespan keeps increasing, meaning that in our lives from now on very few of the social institutions and norms that existed when we were young will exist when we are old.

*

According to Bauman, we see the destabilizing force of liquidity in every sphere of modern life. In the economic sphere, deregulation, “flexible” labor markets, privatization, global finance, international trade, and the dismantling of social protections has fragilized workers’ lives and their communities. In the technological sphere rapid innovations tied to digitization and information networks have made less-educated workers’ training quickly obsolete, shifting them into a new “gig” proletariat with low wages and precarious positions. In the medical field, rapid advances in research and treatment render today’s therapeutic wisdom obsolete tomorrow, leaving less-educated people confused and increasingly skeptical of the medical establishment. And, finally, we see the effects of the liquid outlook in new social and psychological ideologies about the fluidity of identities, particularly regarding gender and sexuality, leaving older people uncomfortable and many young people unsure of which categories they fall into.

*

This is an historically unprecedented situation, as Bauman reminds us, one with profound social and psychological implications. In the most fundamental sense, social institutions exist to offer a stable environment for individuals to develop and cooperate among themselves, and then to transmit knowledge and norms to subsequent generations. Society is by nature conservative, in the sense that its function is to order and conserve. Bauman, a former communist and very much a man of left, was no political conservative. Yet as a sociologist he believed that stable social institutions are necessary for cooperation because they allow people to anticipate the future, and also necessary psychologically for forming a stable sense of self. And he was convinced that the most advanced societies today have reached a tipping point and were ceasing to perform these basic functions, leaving people feeling anxious and unsure about their environment. “There is,” he wrote in Liquid Modernity, “a nasty fly of impotence in the tasty ointment of freedom.”

*

Bauman wrote a number of books (too many, actually) on the theme of liquidity, applying the concept to everything from modern art to modern love. He never wrote one on electoral politics or populism, though, which is a pity since I believe the underlying logic of electoral realignment in the United States and elsewhere has a great deal to do with the phenomena he identified. It also gives us a different way of interpreting the results of the Study Group’s research.

*

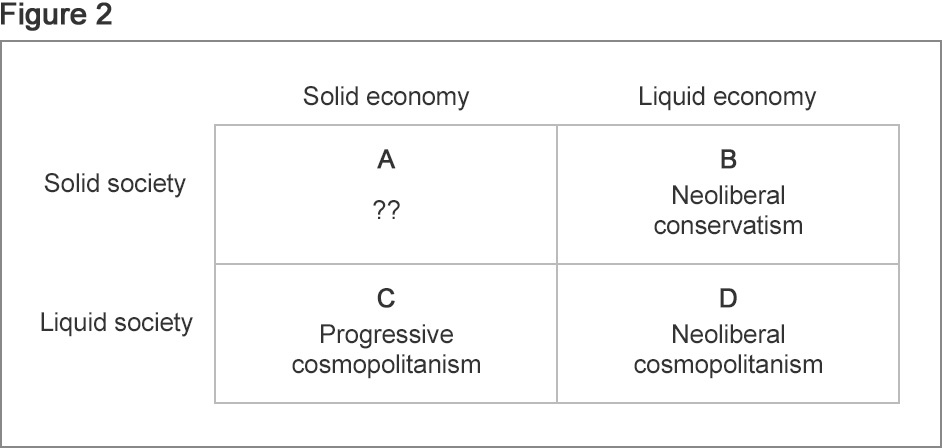

3.The solid party

Imagine a 2 x 2 table with two axes, one reflecting economic views and the other reflecting views on society-identity (shorted to “society”), as in Study Group’s chart (Figure 1). But now let’s label the rows and columns either “solid” or “liquid,” following Bauman, rather than liberal or conservative. This leaves us with four possible ideological positions, indicated by cells A-D in Figure 2. Now let’s examine each cell.

Cell D. This cell represents a consistent pro-liquidity ideology, one that promotes the kind of society Bauman suggested we are already living in. In economics it favors open borders for goods, services, and capital; decreased regulation and taxes; immigrant labor; a focus on growth and lower taxes; and fewer worker protections. On social issues, it prizes individual autonomy, non-traditional families and genders, multiculturalism, and toleration for minorities and immigrants. Call it neoliberal cosmopolitanism.

*

Who occupies this cell? In theory, consistent libertarians – of whom there are very few. Yet paradoxically this is the cell that, if Bauman is right, Western societies seem to be living in or approaching today. There was a short period beginning just after the collapse of the Soviet Union when a utopian vision of a “world without borders” took hold, one in which dangerous national animosities would be abandoned in favor of free trade, free movement of labor and capital, international agreements, and multiculturalism. This “Third Way” had a brief electoral success in the 1990s in the U.S. and certain European countries but it never attracted significant ideological adherents. Instead, we seem to have backed into Cell D, whether due to deep world-historical forces or to a fit of absentmindedness.

*

Cells B and C. Let’s call these ideologies “progressive cosmopolitanism” (C) and “neoliberal conservatism” (B). Both are what Americans call “fusion” ideologies because they are not, from a principled standpoint, consistent. In the United States fusion ideologies started to develop in the 1960s on both the right and left. Traditional religious conservatives began to embrace the ideas of free-market libertarians, and vice versa, transforming the Republicans into the party of neoliberal conservatism – an oxymoron if ever there was one. Still it contributed massively to the Reagan revolution in the 1980s. On the other side, liberals who had been rooted in the working class and labor unions in the post-World War 2 era embraced the libertarian elite social values of the 1960s counter-culture, transforming the Democrats into the party of progressive cosmopolitanism and contributing to the elections of Bill Clinton in 1990s.

*

With a little historical distance we can now see that the Republican and Democratic parties became promoters of both liquidity and solidity, but selectively. The Republicans promoted safety-net free capitalism, despite the fact that the dynamics of the market they celebrated tended to erode social norms and undermine traditional customs and community, placing production and consumption above other social values. The Democrats, for their part, became critics of traditional social customs and authority in the name of individual self-determination and toleration, while at the same time arguing for increased social welfare protections and economic regulations – appeals which to be successful require a public sense of self-sacrifice and the common good. That both fusion ideologies were intellectually self-contradictory did not, however, prevent them from inspiring and sustaining the two major American parties for four decades. The inconsistency of the ideas seemed to reflect the inconsistency of those who held them in society. But the concrete result over those decades was that no matter whether Democrats or Republicans governed, the United States became an increasingly liquid society.

*

Cell A. If this analysis of Cells B-D is correct, we are in a better position to understand those who find themselves in Cell A today. Rather than see them as confused between liberal and conservative positions, we now see them as consistently resisting liquidity and perhaps hoping for a more solid society.

*

In this logic, if one is opposed to free-trade agreements leading to plant closings and the transfer of jobs overseas, it makes perfect sense to oppose immigration and to support social protections. If one values community solidarity, it makes some sense to oppose not only immigration but also to worry about racial and cultural diversity (quite apart from other purely racist or xenophobic motives). If one worries about children’s physical and mental health in families made fragile by the new economy, it could also seem logical to resist ideologies of gender fluidity that might fragilize their sense of self. To state these views is not to endorse them, or to say that one position necessarily entails another. Rather, it is to recognize the strong psychological affinities between these positions if one’s basic disposition is to feel uncomfortable or panicked in an increasingly liquid society. For such people the fusion ideologies of the Republic and Democratic parties would seem much less psychologically compelling.

*

If this interpretation is at all plausible, the Study Group’s findings take on a slightly different meaning. What we are seeing visually in Figure 1 is the migration of voters into a space that has no ideological name and no representation in the major political parties. They are, so to speak, democratically stranded. A populist like Donald Trump, who managed to give voice to many of their fears and resentments, was able to exploit this situation. But that does not mean that the residents of Cell A simply are populists of a Trumpian sort. In another era or in a different country, one could very well see them gravitating either toward a classic conservative party that believed in economic security, or toward a social democratic party with a strong sense of national identity.

*

But those alternatives are simply not on offer in the United States today. And so one can imagine several scenarios for the near future, none particularly encouraging. The most pessimistic is this: as globalization and liquification proceed apace, supported and enabled by educated elites who benefit from the new situation and are comfortable with it, more and more voters not in this class will find themselves stranded and angry. This will provide the opportunity for other, more competent populists to solicit their support, leading perhaps to the creation of a new reactionary political party or force capable of capturing political institutions.

*

Consider what has happened in Eastern Europe: when the political parties formed after 1989 became associated with economic dislocation and cultural liberalization, they were replaced by parties that claimed to resist both. The successes of the Jobbik Party in Hungary and the Law and Justice Party in Poland are not owing simply to demagoguery. In the eyes of many voters, those parties took a coherent stand against the rapid liquification of their societies.

*

Could something similar happen in the United States? It depends primarily what happens within the Republican Party after Donald Trump, since it is unlikely that the Democrats will rethink their focus on society-identity issues any time soon. Trump has managed to drive from the party most moderates who stood for neoliberal conservatism of the Reagan variety, but has failed to rebuild the party either ideologically or institutionally to represent a new, coherent political vision. In particular, he has failed to deliver on most of his economic promises and has provided no alternatives, such as a strong industrial policy to spur innovation and protect American economic autonomy to the degree possible in the age of globalization. He is a destroyer not a creator.

*

Other demagogues wait in the wings. The question is whether out of the ashes of the Republican Party a more serious ideology – call it corporatist or social democratic – will be developed that both convinces voters and provides a responsible and successful script for governing. Some former Republicans are talking about a “National Conservatism” in journals like American Affairs, probably the most interesting new political publication in the United States. It is worth noting that the journal has also attracted a wide range of writers and readers on the European left who still believe in a class-based politics and consider the emphasis on identity politics to be electorally suicidal. Whether a coherent vision will develop in these circles is impossible to know.

*

What we can anticipate, however, is that in the near term the economic and cultural forces that are liquifying our societies will continue to operate, widening the gap between the world we live in and the world more and more democratic citizens dream they could live in. That is never a healthy atmosphere for liberal democracy to flourish.

1 https://www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/political-divisions-in-2016-and-beyond

2 Terms coined by British journalist David Goodhart to distinguish people who are rooted in the places they were born (“somewhere”) and are usually less educated, from those with advanced degrees who participate in a cosmopolitan political culture governed by allegedly universal norms that could be from “anywhere.”

3 That is, people who work with their hands and own small trucks, versus professionals who own an eco-friendly car like the Toyota Prius.

![]()

![]()

|

|---|

- Vol.100 An Arena for Intellectual Opinion and Debate:Commemorating One-Hundred Issues

- Vol.099 Artists Crossing Borders

- Vol.098 A Historical Perspective on the “Chinese Dream”? : The Extent of the Sinosphere in East Asia

- Vol.097 The Ukraine War: A Global Perspective

- Vol.096 Common Sense in Economics, Common Sense in Popular Thought

- Vol.095 Academic Journalism

- Vol.094 Once Again, What Are Today’s Problems?

- Vol.093 A New American Century?

- Vol.092 The “Patchwork” Order Encompassing the World

- Vol.091 The Future as Possibility – Japan in 100 Years

- Vol.090 Redefining the State: 130 Years Since the Meiji Constitution

- Vol.089 The Paradox of Choice of Citizenship

- Vol.088 Special Feature: The End of the Liberal International Order?

- Vol.087 Special Feature: Chinese-Language Literature Beyond China