A Silkpunk Poet-Engineer

By Ken Liu

When I was a child in China—I believe this was when I first started going to school—there was a fairly long walk back home that terrified me: crossing a busy street, making a turn that I could never remember (especially when it rained and made everything look different), passing through a neighborhood where older kids teased the first-graders. My solution for this problem was to walk with other kids in a group. But because I was slow, I had to entice them to stick with me and not leave me behind. My solution to this need was to tell them stories. I spun tales about monsters and rocket ships that kept everyone entertained until we were safely back in our apartment complex, and sometimes we even huddled in the yard before going home so I could finish a particularly exciting story.

*

Every writer has an origin story like this—it's necessary to have one ready because you always get asked "how did you become a writer" at some point. Sometimes, the origin story might even come close to being true.

*

I don't think writers mean to lie when they tell their origin stories, but these stories are also rarely 100% factual. Events are left out; details embellished; long periods in real life artfully refined into inspirational montages; the role of luck de-emphasized or cleansed from the account altogether; and satisfying causes and effects attributed to what, in reality, were just one random thing happening after another.

*

We can't help imposing the shape of a plot to the chronicle of accidental events that make up our lives.

*

In my case, I have only the vaguest memories of that early period of my life, and it's hard to separate the real memories from re-created memories based on the accounts of my grandparents—they told me that story when I showed an interest in writing fiction. The fairy-tale-like structure of the narrative—a journey through an urban equivalent of the dark woods, filled with dangers that had to be overcome and companions that had to be won over—suggests fictionalization, but it's hard to know for sure.

*

As a species, we have evolved to understand the world and ourselves through stories. This gives fiction writers job security, but it also means that we need to be careful about words like "truth" and "fact." The former is an understanding of the world while the latter is an observation about the world; neither is free from the effects of the unique cognitive terrain of the understander or observer. We are the heroes of our own life stories, and we are prone to all the biases that vantage point entails.

*

This does not, however, absolve us from the duty to seek truth or the commitment to honor facts. I don't see the always-mediated nature of reality as implying that all understandings or observations are equally valid. Although we're all blind to the elephant that is reality, there is a difference between describing the elephant under our probing fingers through the best metaphors we can think of and throwing up our hands to willfully insist that the elephant is the exact same thing as a serpent, even though we have already touched the sharp points of the tusks.

*

Because of our cognitive reliance on stories, it's important to maintain both a love and a skepticism toward them. National myths, being stories that a people tell themselves to explain who they are and how they're different from everybody else, can both be the basis for revolutionary movements to throw off the yoke of imperial and colonial oppression, but can also lead to militarism and terror. Cities, families, professions, even individuals have smaller-scaled stories, mythical narratives that define our identity and our relationship with others. Stories sway our empathy and creep into scientific explanations for data. Stories decide court cases and provide justification for our faith. Stories move and motivate, comfort and admonish, confuse and illuminate, inspire and conspire—we are, in a word, made up of stories.

*

To find the story that empowers us and illuminates reality is the only ethical duty of art that I find compelling. It is a duty that suffuses everything I do.

*

Science Fiction and Fantasy

I'm often described as a writer of science fiction and fantasy, but these are marketing labels that don't mean much. Rather, I think of myself as a writer of fiction in which metaphors are literalized, endowed with concrete existence.

*

I've held many jobs and pursued three careers: programming computers, practicing law, and writing fiction. The three endeavors are not as distinct as they might appear at first glance—all involve the construction of artifacts out of symbols (programs, contracts, stories), which then, pursuant to the rules of the system, produce specific results.

*

A program achieves the result desired by the user by following the rules of boolean logic and computer circuitry; a contract achieves the parties' desired result by following the rules of the legal system; a story, on the other hand, achieves the emotional result desired by the writer by following the rules of narrative.

*

Much of our economy these days involves such symbolic manipulation and the caring and feeding of symbolic machines. Finance, law, science, business consulting—we pay people to be good symbolic engineers.

*

But there is an abstract quality to symbolic manipulation that can be alienating. Working with symbolic machines is, after all, not quite the same as working with physical machines. We are embodied creatures who evolved to know the world through our physical bodies and imperfect senses. We crave the concrete, the tangible, the numinous made incarnate.

*

Even mathematics, that most abstract of the sciences, benefits from concreteness. I loved geometry as a child, especially the part that involved construction of triangles and bisecting angles using nothing more than a straightedge and compass. It's too bad that so many schools now seem to have abandoned this pedagogical approach.

*

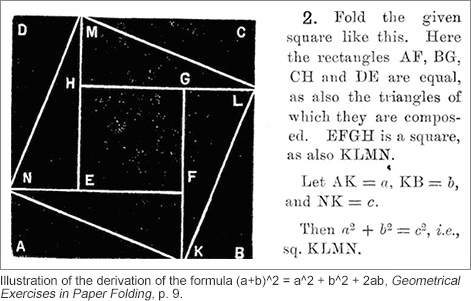

I was gratified to discover that in 1893, the Indian mathematician T. Sundara Row published Geometrical Exercises in Paper Folding, which tries to teach geometry through the ancient art of origami. Instead of merely following through the steps of a proof as generations of children have been taught to do, readers of Row's book are instructed to literally construct the figures out of paper, and, by folding, tucking, creasing, unfolding, bending, crimping ... discover the wonders of arithmetic and geometric series, the Pythagorean Theorem, Zeno's Paradox, algebra, and even conic sections.

*

Manipulating physical objects has an effect on the mind that cannot be replicated in logical deduction through symbols. The pleasure of folding paper and watching a truth emerge teaches in a way that meticulous and elegant proofs cannot.

*

This is also why I'm drawn to writing science fiction and fantasy—these are genres in which abstract metaphors are made tangible, so that we can manipulate and examine them in our minds and come to a new understanding.

*

Suppose we're interested in exploring the alienation of modern life, a state of existence in which most of us live in large cities, navigate an impersonal concrete-and-glass jungle to our cubicles, conduct conversations pursuant to scripts dictated by our superiors, and are surrounded by millions of strangers every day. It's easy to experience a sense of disconnectedness, a feeling that the inner lives of the strangers we brush by on the subway, in the street, on the escalators are inaccessible, that they are, in some ways, not fully human—and what does that say about our own capacity for empathy, which evolved in a tribal context but must now be deployed to engage with the pains and problems of millions, many of whom we never see?

*

A realist fiction writer might delve deeply into the inner psychological life of the POV character and treat that stream of consciousness as the only reality we can count on, with others dipping in and out of it as metaphorical mechanical shells devoid of the ghost of true awareness (much of Modernism may be reductively classified in this mode).

*

But a science fiction writer would approach this differently. They might decide to make the metaphor of alienation, of the inaccessibility of other minds, of the perception of being surrounded by shadows of humanity into a literal truth. They might posit a world in which some strangers are in fact not human, but only pretending to be. They pass as humans, brushing by us in the neon-lit night, stride through smog- and rain-drenched cityscapes, speak and laugh and cry and recite poetry about the shoulder of Orion—but only in imitation of the real thing, for they are in fact machines devoid of empathy, the one foundational emotive faculty that defines humanity. To screen out the real from the unreal, the soulful from mere replicants, a scientific test must be devised to measure empathy.

*

I am, of course, talking about Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, one of the first science fiction novels I read as a child, and better known to many as the film Blade Runner. (Incidentally, when I first read this book, I had no interpretive framework for reading it as a piece of speculative fiction. Therefore I approached it as a realist book, and you can imagine the confusion and interpretive gymnastics I had to go through to make sense of it.)

*

The science fictional approach is not better or worse than the realist approach, but it is a different way to tell a story. By making the metaphor of alienation and the difficulty of making connections concrete, it allows us to explore these subjects, both emotionally and intellectually, in a distinct way. These divergent literary modes offer different insights, lead to different emphases, and compel us to get a feeling for the central experience of modernity—an intense loneliness in the midst of an ever-expanding crowd—that is otherwise impossible.

*

Since I brought up origami earlier, I'll add a few words here about "The Paper Menagerie," perhaps my most well-known story. This story uses the fantastic vision of origami animals coming to life to literalize a set of metaphors about mother's love, the pressure to conform, and the importance of valuing the feelings of those who love us—the only magic we can count on. It's often mentioned as the first story that won the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy Awards, but I don't much care about those accolades—the fact that readers from across the world have written to me to tell me how much the story moved them and how they saw glimpses of themselves in the guilt and regret of the son and the strength and selfless love of the mother has been far more gratifying to me.

*

To me, the fundamental purpose of stories is to empower readers through an emotional and intellectual experience that allows them to live another life. It is a virtual reality deeper and more immersive than the most wondrous offerings of modern technology.

*

Silkpunk

By now it should be obvious that I don't think science fiction has much to do with the future—although I am a technologist by training and profession, I don't think futurism is the primary purpose (or even most interesting aspect) of science fiction. The way that science fictional metaphor-literalization can cast a new light on the present is far more compelling to me.

*

But that doesn't mean I don't enjoy engineering. Engineering, in fact, has always been a vital part of how I work, in fiction or otherwise.

*

A transformative book for me was W. Brian Arthur's The Nature of Technology. In it, Arthur upends the conventional view of engineering as a mere handmaiden to science, but treats it as an independent art that is responsible for the bulk of our technological progress.

*

Engineering, in Arthur's conception, turns out to be a lot like composing poetry. Just as poets fashion poems to achieve novel emotional effects via innovative combinations of tropes, rhyme schemes, forms, stanza patterns, blasons, allusions, refreshed clichés, unexpected associations between stock objects, engineers solve problems with new inventions by innovatively combining known technologies and components in novel variations. A poet's work is subject to all kinds of constraints: space, form, sound, tradition, and must exhibit throughout a quality of elegance and beauty. An engineer's work, similarly, is constrained by material, cost, space, efficiency, and must exhibit the same qualities of elegance and purposive beauty. Anybody who has studied programming in some depth or gazed at Steve Wozniak's circuit boards would not doubt that there is poetry in engineering.

*

The idea of technology as a kind of language was the inspiration behind my silkpunk aesthetic, embodied in the Dandelion Dynasty (蒲公英王朝記 in Japanese) series of books (The Grace of Kings (2015), The Wall of Storms (2016), and a third book, yet to be published).

*

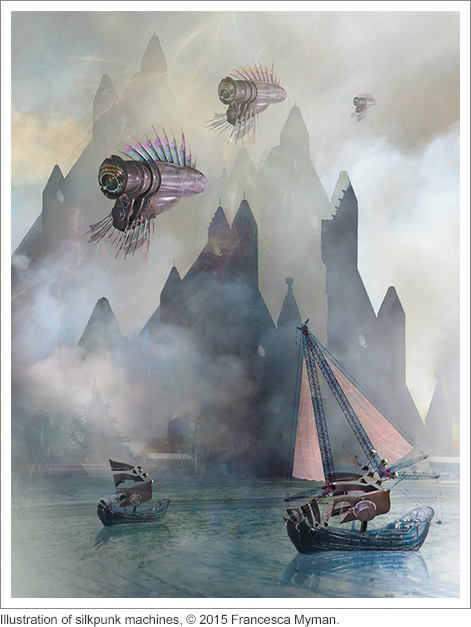

Silkpunk, like steampunk, is a fantasy mode based on a particular technology language. But whereas steampunk takes as its basis the technology language of the Victorian Era, silkpunk takes as its inspiration the engineering language of East Asia's antiquity, especially as presented in the amazing legendary inventions described in historical romances and narrative poetry.

*

Just as the technology vocabulary of steampunk consists of gleaming brass, polished glass, weathered leather, and steam-blasted iron, the technology vocabulary of silkpunk consists of paper, silk, wood, animal hide and sinew, bamboo, and other material of importance in East Asian history. The technology grammar of silkpunk, moreover, honors the East Asian philosophical tradition of emphasizing the harmony between humanity and nature in engineering and construction by prioritizing biomimesis as a technique.

*

The Dandelion Dynasty is an attempt at deconstructing and re-imagining a foundational narrative, the legends surrounding the founding of the Han Dynasty, in a fantasy world populated by giant mythical whales covered in adamantine scales and where the gods intervene in human affairs as easily as superheroes in today's films. Although the books are presented as fantasy and written in a style that is a blend of the great Western epics (e.g., the Iliad and the Aneid) and Eastern historical romances (e.g., Romance of the Three Kingdoms), the novels are, at their heart, a philosophical adventure in which the great heroes are poet-engineers like the beloved Zhuge Liang, whose elegant inventions changed the course of battles and the fates of nations.

*

This is a world that features giant battle kites that carry dueling heroes into the sky; silk-and-bamboo airships that propel themselves through the starry empyrean like glowing, pulsating jellyfish; steam-powered submarines that swim through the ocean like whales; new weapons and engines of commerce powered by a mysterious force that is generated by pieces of silk rubbed against glass.

*

Neither is the technology of my world limited to machinery. The Dandelion Dynasty also explores the technologies of politics and social engineering. Philosophies of administration and empire-building contend in debates and state-wide examinations, and heroes must win as much on the battlefield as in the arena of institutional reform and political innovation. In this fluid society in transformation, bandits and scions of noble clans must ally against a corrupt empire, and a young princess and a farmer's daughter forge an unlikely friendship that will remake the world as they know it.

*

At their heart, these books are fantasies about engineering, and they hint at my belief that the most wondrous magic in our world is made manifest through engineering.

*

Learning To Be a Novelist

Once I had the vision of a world large enough for my epic story, I still had the challenge of implementing it.

*

Before I wrote my novels, much of my reputation as a writer of speculative fiction was built upon the foundation of short stories.

*

To date, I have two short fiction collections in Japanese, published by Hayakawa(“The Paper Menagerie and Other” , “MEMORIES OF MY MOTHER AND OTHE R STORIES”). These represent but a small portion of the 130+ stories, novelettes, and novellas that I've published over the years. Most of these stories are under 5000 words, and dozens are under 1000.

*

When you've honed your craft by writing 1000-word flash fiction stories, how do you learn to write a 200,000-word novel?

*

I thought that if you added up all the stories I'd ever written, you'd end up with a novel of about the right length. How hard could it be to just do what I've always done, except more of it?

*

Contrary to my expectation, writing short fiction turned out to be a very different exercise from writing a novel. A 200,000-word novel was not, in fact, just 20 1000-word flash stories strung together.

*

Since I love metaphors, that's how I will explain this difference. A flash story is like a mosquito, while a novel is more like an elephant. It is simply not true that you if scale a mosquito up to the size of an elephant, you'd have a viable creature.

*

This is because the body plan of an insect is fundamentally different from the body plan of a large mammal like an elephant, and the laws of physics function differently at these scales. An insect lives in a world where gravity is not the dominant force, and due to the relative large ratio of surface area to internal volume at its size, can function entirely by "breathing" passively through its spiracles. An elephant, on the other hand, lives in a world dominated by gravity—thus requiring a strong skeleton for internal support—and the mathematical fact that volume grows as a cube of length and surface area grows only as a square of length means that the elephant must have a complicated active respiratory and circulatory system to oxygenate its internal tissues. A mosquito scaled up to the size of an elephant would collapse and suffocate. Physics thus imposes an upper limit on the size of an insect.

*

(Indeed, the fact that insects during the Carboniferous Period were so much larger than their present counterparts is in part explained by the higher oxygen content of the atmosphere during that time.)

*

Similarly, short stories are structurally different from novels, and it's impossible to scale up a narrative constructed along plans best suited for short fiction and expect to have a viable novel. For one thing, short stories often don't require much plot (witness my story, "The Bookmaking Habits of Select Species," collected in the Japanese collection “The Paper Menagerie and Other”), but a novel without plot is a creature that cannot breathe. Short stories can also get away with very simple structures and perhaps a single plot line, but such a structure cannot support the weight of a narrative of 200,000 words. Sophisticated readers today—unlike their predecessors from the Carboniferous Period (or when the first novels were written centuries ago)—have been trained on a diet of complex TV dramas and multi-POV, fragmented narratives in electronic media. They expect such complexity and layering in novels, where the narrative energy is supported by multiple plotlines and many well-developed characters.

*

After I threw away my preconceptions and started anew, learning to write a novel became an extremely satisfying experience. I had to learn a new way of engineering words and stories, and came away as a different kind of writer.

*

Now I have trouble writing short! When asked to write a novelette of 10,000 words, I sometimes think: That's barely enough to introduce a single character! How am I supposed to tell a whole story with so few words?

*

Translation

An overview of my writing life wouldn't be complete without mentioning my role as a translator.

*

For most of my writing career, I had no interest in translation at all. It seemed to me a mechanical process that required little creativity.

*

However, as I explored world SF—I loved the work of Taiyo Fujii and Project Itoh—I also began to read Chinese SF. I was extremely please to discover Chen Qiufan (陳楸帆), an extremely accomplished writer who also became my friend. Chen had helped introduce my fiction to Science Fiction World, China's most prominent SF magazine, and I marveled at his stories, which displayed an encyclopedic knowledge of both the West and East, as well as a deft style that masterfully combined the stately beauty of Classical Chinese with the suppleness of contemporary, Western-inflected stylistic innovations derived from modernism, post-modernism, and the visual arts.

*

Chen deserved a wider audience in the world, and I was excited when I found out that one of his stories, "The Fish of Lijiang," had been translated into English. But reading the draft translation was disappointing. Although the translation was technically accurate, the witty, sardonic voice that offered up mordant observations, the voice that made a Chen Qiufan story so unique, was gone.

*

Though I had never done any translation, I offered to fix the translation for my friend. But shortly after that, I realized that it was easier to do the translation from scratch than to edit someone else's work into what you wanted. I threw away the old translation and embarked on my first attempt at re-creating the work of another writer for a new audience.

*

As I studied and practiced literary translation, I found it to be yet another form of engineering. It is like an attempt at recreating a machine constructed from brass, leather, and glass with bamboo, paper, and silk. Not only do I need to find substitute materials, I also need to consider the strengths and weaknesses of the respective materials, the landscape in which the new machine must function, and the engineering principles that hold sway in the new environment. To change the metaphor somewhat, I had to engineer a bridge—subject to all sorts of constraints—between two literary traditions and two sets of cultural expectations. When done well, a translated work takes on a new life, and a fresh, unique voice gains a new audience.

*

Since that first attempt—which won Chen Qiufan and me a Science Fiction and Fantasy Translation Award—I've translated dozens of stories. Some of my favorite translations are collected in the anthology, Invisible Planets (2016), the first English-language anthology of contemporary (that is, post-2000) Chinese Science Fiction.

*

I've also had the honor of working on volumes one and three of Liu Cixin's SF masterpiece, the Remembrance of Earth's Past trilogy. The first volume of the series, The Three-Body Problem, was the first translated work in history to win the Hugo Award, the premier award for science fiction and fantasy in the English-speaking world (and sometimes considered the greatest award in world SF).

*

Doing translations is part of my service to the community of writers and readers across the world, a part of how I honor stories. And it has taught me much about the beauty that translators bring to the world.

*

My fiction has won the Seiun Award in Japanese, but much of the credit for that should go to my Japanese translator, Yoshimichi Furusawa. When you read my stories in Japanese, you are hearing my voice as expressed through the words of Mr. Furusawa. It is the beauty of his Japanese symbolic machine, based on my English machine, that is responsible for your emotional experience.

*

I have had a very blessed life as a writer. I get to tell stories that I love to people who find beauty in them. Many of my stories explore the terrors and atrocities of our history, but I am, overall, an optimistic person. I believe that it's possible for all of us to connect, to share and empathize with each other's stories.

*

Given the intense interiority of our individual experiences and the loneliness that is the essence of the human condition, every act of communication between husband and wife, between brother and sister, between mother and son, between friend and friend, and between reader and writer, is a miracle of translation, of empathy, of intersubjectivity. It gives me hope for our species to see how much we yearn to connect, and how often, despite all our foibles and the cold, uncaring equations of this universe, we succeed.

![]()

![]()

|

|---|

- Vol.102 Academic Journalism II

- Vol.101 The COVID-19 Pandemic Through the Lens of Economics

- Vol.100 An Arena for Intellectual Opinion and Debate:Commemorating One-Hundred Issues

- Vol.099 Artists Crossing Borders

- Vol.098 A Historical Perspective on the “Chinese Dream”? : The Extent of the Sinosphere in East Asia

- Vol.097 The Ukraine War: A Global Perspective

- Vol.096 Common Sense in Economics, Common Sense in Popular Thought

- Vol.095 Academic Journalism

- Vol.094 Once Again, What Are Today’s Problems?

- Vol.093 A New American Century?

- Vol.092 The “Patchwork” Order Encompassing the World

- Vol.091 The Future as Possibility – Japan in 100 Years

- Vol.090 Redefining the State: 130 Years Since the Meiji Constitution

- Vol.089 The Paradox of Choice of Citizenship