- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

Suntory Museum of Art 60th Anniversary Exhibition

Unsettling Japanese Art

July 14 to August 29, 2021

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition.

*Download the list of changes in works on display

*Photography is permitted at this exhibition, except for some works.

The list of changes in worksPDF

Section 1

Behind the Behind—Let’s See the “Other Side” of the Work!

Here’s a work always displayed with its front facing the viewer. Turn it around or upside down, though, and you’ll be surprised. An unexpected aspect—or aspects—await. That hidden face can teach us much about the hidden true nature of the work.

For example, let’s take a look at the Top-shaped Bowl with Five Ships Design in Overglaze Enamels, an Important Cultural Property from the late Edo period. Inside and outside the bowl we see a design of five Dutch ships. When you turn it upside down, though, and you’ll see one Chinese character has been inscribed on the underside of the foot, 寿, kotobuki, “long life and good fortune.” Back in the Edo period, people respected the Dutch ships that crossed the seas, bring treasures to Japan, and called them takarabune, treasure ships, likening them to the mythical ship bearing the seven gods of good fortune and myriad treasures that is used as symbol to attract good luck. The 寿 character can thus be thought to symbolize the auspicious nature of this bowl.

In this section, we have experimented with displaying a variety of works—ceramics, Noh masks, folding screens, textiles—so that their hidden faces are also visible. Enjoy exploring the information visible on what is usually hidden, including the superb skill of the work’s creator and the distinctively Japanese aesthetic that takes as much care in creating a work’s back as its front.

(Important cultural property)

Arita, Edo period, 18th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Section 2

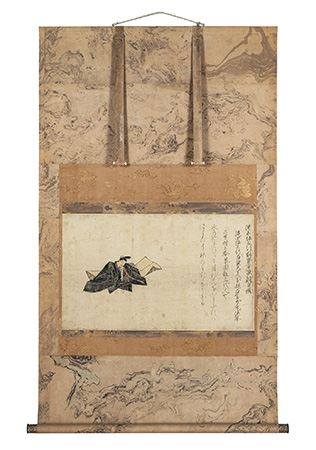

Snip, Snip—Cut Up and Reconfigured?

The work you see today may not be in its original form. Surprisingly enough, many works of art have a history of being cut into segments.

Consider Portrait of Minamoto no Shitagō, from the Satake Version of the Thirty-six Immortal Poets, one of the famous paintings in our collection. Today its gorgeous mounting as a hanging scroll draws the eye. Until about a century ago, however, the painting was part of a set of long handscrolls. In Dancers, paintings of six women dancing, each holding a fan, each of the six is framed separately. Originally, however, it is said that they adorned a six-panel folding screen.

This section brings together works thought to be in altered form: from a handscroll to a hanging scroll, from a folding screen to a framed painting, from the cover of a comforter to a detached segment of treasured fabric. Here we display these works in ways that aid in imagining their original form. We also touch on the thinking, the context in which these slices were made, and the thoughts and feelings of the people involved.

(Important cultural property)

Painting attributed to Fujiwara no Nobuzane, calligraphy attributed to Gokyōgoku Yoshitsune

Hanging scroll, Kamakura period, 13th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Shōwa period, 20th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between July 14 and Aug. 9】

Section 3

Take a Closer Look—Surprising Discoveries Await!

It’s easy to say, “Take a good look at it,” but not so simple to do it. But when you’re enjoying the experience of looking really closely, you’ll discover things that were not visible if you just glanced at a work.

For example, the takarazukushi, “myriad treasures,” is a collection of Japanese traditional auspicious motifs often embroidered on koshimaki over-kimono. Look closely, though, and you will see that these motifs include many items we would hardly call treasures today. It’s a collection full of odd things. Or consider the Large Dish with Phoenix Design in Overglaze Enamels. The giant phoenix in the center tends to take over our eyes. But look carefully at the area around it and you will see, nearly hidden, a variety of auspicious motifs against the dark purple background.

This section introduces works in which you’ll want to scrutinize every nook and cranny. You’ll detect parts so delicate they’re almost invisible, pieces that aren’t visible because they’ve fallen off, parts you can’t understand unless you really use your imagination and intuition.

Edo period, 19th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between July 14 and Aug. 9】

Arita, Edo period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Section 4

Take It Apart—What if You Dismantle a Work?

Once apart, you realize for the first time how much we matter to each other……that experience applies to works of art, too. Yes, think of the body and lid as equals. If we dare to separate pieces of what were originally a set and look at them, side by side, what might we discover?

This section presents a variety of works that are sets, composed of a body and a lid, including ceramics, lacquerware, and metalwork with rather unusual lids. Consider the Writing Box with Seashell Design in Maki-e. What’s different from the usual approach to displaying it is that the box is shown with the body and lid at a certain distance from each other.

Separating them makes it possible to probe their differences in motif, form, and technique and to deliberately consider the significance of their being a set. You may be able to notice the calculated peculiarities of a set’s design—effects that can astonish those using the work.

Ogawa Haritsu

Edo period, 18th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Satsuma, Edo–Meiji periods, 19th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

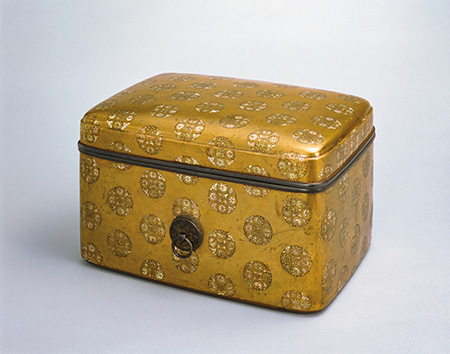

Section 5

Box, Boxes, Boxed—Secrets of the Containers for Works

If works as we see them in the gallery are “on,” “at work,” then what is “off,” their resting state? In the case of classic Japanese art, works usually rest, wrapped in comforter-like padding, in boxes made of wood or other rigid materials. Step into the storeroom where works are kept, and you will see box after box—rows of nothing but boxes.

In this section, we introduce the little-known world of the box. These containers, designed to protect valuable works of art from external impact, come in many sizes, shapes, and materials. Boxes may also carry inscriptions that influence the value given to a work. And boxes can go beyond their original function to be so beautifully decorated that they surpass the artwork within—truly putting the cart before the horse.

Are you a box fancier who collects lovely candy boxes? Even if you are not, do enjoy exploring this aspect of Japan’s distinctive container culture.

Gyōen

Kamakura period, dated 1215

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

(National treasure)

Kamakura period, 13th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

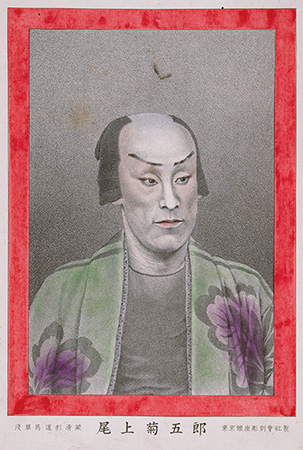

Section 6

Unsettling—“Beautiful” Doesn’t Make It Art

Japanese art may seem understated. It’s often thought difficult to appreciate, too. But it actually includes many works that are quite disconcerting.

For example, Onoe Kikugorō, a lithograph of an actor dating from the early Meiji period, is filled with almost incongruous liveliness. In the Priest in a Bag handscroll, one of our museum’s secret treasures, a man’s rather creepy face is appearing, just slightly, from under a bag, behind a woman with her hand on her chest. And then we have Plum Blossoms in Sumi Ink, by Itō Jakuchū, a painter known as an eccentric. He has deformed the motif so radically that, if we didn’t know the title, we’d never guess what was being depicted.

There is no reason that a work of art has to make us feel it’s beautiful—or that something beautiful has to be a work of art. Here let us explore the depths of Japanese art, depths containing works that unsettle, disconcert, and arouse us in many ways.

Meiji period, dated ca.1875

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Handscroll, Edo period, 17th–18th centuries

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2024 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

2024 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31