- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

Prayers to Water

December 16, 2015, to February 7, 2016

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition

Section 1

The Power of Water

Water is the source of life and has great power that brings many blessings to the world. As such, water became the object of worship early in history. In Japan this early reverence can be seen in the flowing water design on the dotaku (ritual bronze bells). Pure water is revered in a religious context as having sacred powers and thus also came be used in rituals. Purification, boiling of fresh pure water and waterfall are some of the examples of how water is used in ritual settings, with the most famous in Japan the Omizutori (Water-Drawing Festival) held annually at Todai-ji.

Conversely, a look at the histories and legends of Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples reveals many incidents linking water to the origins of their principal image of worship. In some instances the Buddhist statue, the central image at a temple, has appeared in water, or has been carved from a piece of sacred wood that floated across the sea. In each instance the mystical power of water heightens the spiritual power of the statue. A major example of this phenomenon can be seen in the Eleven-headed Kannon (Avalokitesvara) at Hase-dera, whose spiritual power was then re-created in Hase-dera style Eleven-headed Kannon replica statues produced for temples throughout Japan.

This section introduces works that are examples of the mystical power of water, ranging from Buddhist and Shinto objects to temple and shrine histories.

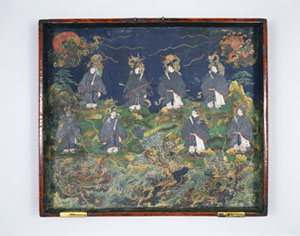

Important Cultural Property

Landscape with Sun and Moon

Muromachi period, 15th-16th century

Kongo-ji, Osaka

Standing Eleven-Headed Kannon (Ekadasamukha Avalokitesvara)

By Chokai

Kamakura period, 13th century

Paramita Museum

Photo by Kenji Yamazaki

Section 2

The Gods and Buddhas of Water

As worship increased, water was gradually deified to the point where water was viewed as its own Shinto or Buddhist deity. Examples of this development can be seen in the Buddhist deity Benzaiten, today renowned as one of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune in Japan. Originally Benzaiten was the Hindu deification of rivers in ancient India known as Sarasvati. Today worship of Benzaiten primarily remains in water-linked or water-rich areas, whether islands surrounded by water or sites of natural springs. This section introduces the Benzaiten images worshipped at such ancient water-centric worship areas as Enoshima, Chikubushima, Tenkawa and Itsukushima. In particular, this exhibition presents a rare opportunity to see the uncanny deity Ugajin, often syncretized with Benzaiten, in the special showing of the Ugajin statue from Honzan-ji, Osaka.

This section displays the various forms of water-related Shinto gods and Buddhist deities, including ancient Japanese-origin water gods, Sumiyoshi-Myojin, a Shinto deity worshipped as the god of sea passage, Komori-Myojin who was originally Mikumari-shin, the deity who governed water distribution, and images related to Iwashimizu Hachiman shrine, named after pure water welling up from there, long renowned as a water-linked site.

Section 3

Prayers to Water

Prayers for rain, an essential element of growing rice and other grains and thus linked directly to national welfare, are at the core of the worship of water, and in Japan the majority of prayers for rain rituals feature Ryujin, the dragon deity. Ryujin legends survive today in various parts of Japan, and the deity also appears in numerous narrative tales, making this deity particularly well known. Large numbers of Ryujin-related artworks remain, from painted and sculpted images of the deity itself to decorative artworks featuring the deity's attributes, including the dragon's jewel. This immense number of extant works conveys both a sense of the flourishing of Ryujin worship, along with showing how keenly people prayed for rain.

The Buddhist sutra known as the Lotus Sutra also includes a scene in which the Ryujo, the Dragon King’s daughter presents a jewel to Sakyamuni and becomes a Buddha. Another scene recounts how water-related worship explained a survivor’s salvation from a shipwreck. Such sections of picture scrolls produced against the background of deep faith in the sutra and gorgeously decorative sutras in the Heian period.

This section presents imagery related to prayers to water, focusing on prayers for rain, while introducing materials related to rain prayer rituals and altar arrangements for such prayers, and works featuring Ryujin.

National Treasure

Dragon King (Nagaraja) Zennyo

By Jochi

Heian period, dated 1145

Kongobu-ji, Wakayama

Nested Boxes for a Wish-granting Jewel with

Scenes of Kasuga and Dragon Deities (part)

Nambokucho period, 14th century

Nara National Museum

Image courtesy of Nara National Museum,

Photo by Kinji Morimura

Important Cultural Property

Nested Boxes for a Wish-granting Jewel with

Scenes of Kasuga and Dragon Deities (part)

Nambokucho period, 14th century

Nara National Museum

Image courtesy of Nara National Museum,

Photo by Kinji Morimura

Important Cultural Property

Kujakukyo (Mahamayuri Sutra) Mandala

Kamakura period, 13th century

Matsuo-dera, Osaka

Section 4

Water Utopias

Since antiquity, people have imagined and depicted various forms of utopias. These have included Buddhist sacred lands across the sea, the utopian Mt. Horai floating on the sea, or Dragon Palace under the sea. Indeed, many of the utopias are surrounded by water. The sacred water, the boundless sea that both protects the utopian realm and at the same time promises fecundity, can be seen as the boundary between this world and that sacred land. Such beliefs have in turn led to many images of utopias. This section introduces works featuring water-related utopias, such as the Buddhist “Pure Lands,” Mt. Horai and the Dragon Palace. Many of the major Buddhist deities have their own paradises known as Pure Lands, and in Japan the two major Pure Lands that appear in artworks, as seen here, are those associated with the Buddha Amida and the bodhisattva Kannon. Mt. Horai (Ch: Penglai-shan) is a utopian realm based on ancient Chinese immortal worship, and in Japan Mt. Horai imagery took on an auspicious character, leading to its frequent appearance on decorative artworks. Folk tales have long told the story of the Dragon Palace, the underwater palace of the Dragon King, and images of this palace frequently appear in narrative pictures, such as the handscrolls depicting the Japanese Shinto mythology of Umisachihiko and Yamasachihiko, and the tale of Amewakahiko who is the Dragon King of the Sea, and the Noh play Taishokkan.

Tebako Box with Mt. Horai Design in Maki-e

Nambokucho period, 14th century

Suntory Museum of Art

Section 5

Water and Good Fortune

Water is the source of prosperity, and hence has always been linked with good fortune. As a result, many images of water appear in auspicious designs and motifs. For example, the Chinese historical event that immortality could be achieved by sipping the dew on chrysanthemums led to the so-called kikusui (chrysanthemum water) motif. This meant that images of chrysanthemums f loating on f lowing water appeared on many different forms of decorative arts, all symbolizing longevity. Of further note is the use of waterfalls in design motifs. Waterfalls themselves have long been revered as deities in their own right and Kanbaku (viewing waterfalls) have been highly valued for many years. Images of the waterfalls themselves and their designs can thus be understood to have auspicious meaning.

This section focuses on auspicious designs, as seen in the utensils used in such festive settings as weddings, and examines all of the ways that images of water have been imbued with auspicious meaning and then used to adorn the paintings, decorative arts, textiles and other equipment of daily life.

Cups with Tortoise and SeaShell, Design in Maki-e

and Cupstand with Waves and Mandarin Ducks

Design in Mother-of-Pearl and Maki-e

By Nagata Yuji

Edo period, 18th century

Suntory Museum of Art

Green Maple Leaves and Waterfall

By Maruyama Okyo

Edo period, dated 1787

Suntory Museum of Art

Section 6

Sacred Water Sites

Temples and shrines were built at sacred water sites and came to be centers of worship. For example, the founding of Shitenno-ji by Shotoku Taishi (574-622) was closely linked to water, and indeed a sacred spring wells up beneath the temple’s Kondo. The stone gate in the temple precincts is thought to be the eastern gate of a Buddhist Pure Land, and thus worship suited to this sacred water site continues today. Towns grew up around these sacred water site temples and shrines, which became integral to the daily lives of the residents. Areas blessed with abundant water sources also saw the growth of cities, and festivals related to water are still found in Japan, such as the Gion Festival in Kyoto and the Sanno Festival of Hie-Taisha on Lake Biwa. In Japan’s pre-modern era sacred water sites also began to appear in pictures of famous sites, urban imagery and festival imagery, all means of conveying the splendor of these sites to later generations.

The final section of this exhibition stands as an epilogue, presenting folding screen works that depict people living with water in these sacred sites.

Muromachi period, 16th century

Suntory Museum of Art

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2024 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

2024 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31