- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

The Maestro of Conception, KENZAN is here

May 27 to July 20 2015

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition.

Section1

The Road to Kenzan ― Kyoyaki`s Origins and Seventeenth Century Kyoto

Ogata Kenzan, a child of the Kariganeya,a wealthy Kyoto kimono merchant household, was born in 1663.The Kariganeya were prosperous and prestigious merchants whose patrons included the wife of Tokugawa Hidetada, the second Tokugawashogun, and his daughter Masako, who became Tofukumon`in, the wife of Emperor Go-Mizunoo.The family had been involved in the arts for generations and were related to the illustrious Hon`ami and Raku families of artists and craftsmen. Growing up in that environment deeply infused with culture had a major impact on Kenzan`s aesthetic sensibility.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, during the Momoyama and early Edo periods, ceramics from many pottery centers were booming in Kyoto, stimulating the launch of pottery production there. In recent years, as the technical genealogy of Kyoyaki, Kyoto ware, has become clear, we have realized that the Kenzan kiln was rooted in the Kyoyaki, tradition that included Oshikoji-yaki and the work of Nonomura Ninsei.

Kenzan ceramics were created by directly linking the aesthetics of Kyoto`s affluent merchant class with the Kyoyaki tradition.

Section2

Kenzan`s Dashing Entry ― Large Planes and Japanese and Chinese Inspirations as the Dual Foundations of His Work

Kenzan, having had, from his youth, a strong desire to live in seclusion, retreated to live near Ninnaji temple in 1689, beginning a life as a cultured recluse. Nonomura Ninsei`s Omuro kiln was nearby, and Kenzan apparently studied ceramics with him. Then in 1699 he built his own kiln in the Narutaki Izumitani area northwest of Kyoto. Deciding that the time had come, he began to work professionally as a potter. The kiln`s name, Kenzan, is derived from its location, northwest(ken)of Kyoto.

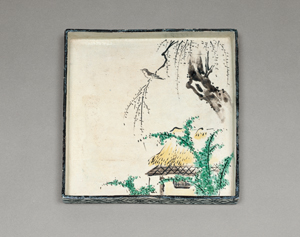

One of the distinctive types of ceramics Kenzan produced at his kiln in Narutaki is the square dish, which resembles in format the picture plane in a hanging scroll. With the large planes his new format afforded, he was not decorating a dish with a painting but making a painting itself a piece of potter a complete reversal of the usual thinking. In addition, his use of literary and painterly images, in both his works in overglaze and underglaze enamels, which resemble classically Japanese Yamato-e paintings based on waka poems, and in underglaze iron oxide, whose brownish hues resemble suinoku-ga, monochrome ink paintings based on Chinese poems, successfully drew a vivid contrast between Japanese and Chinese styles unprecedented in Kyoyaki. Use of both Japanese and Chinese themes became the dual foundations of Kenzan`s work.

Square dishes with seasonal motifs based

on Fujiwara Teika’s poems of the twelve months,

in underglaze enamels

Ogata Kenzan Edo period (1702)

MOA Museum of Art

Sake cup stand with balloon flower design in overglaze enamels

Ogata Kenzan Edo period (18th century)

Miho Museum

Square ember pot with landscape design in underglaze iron oxide

Ogata Kenzan, pottery; Ogata Korin, painting Edo period (18th century)

The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

Section3

Replicas ― The tradition Sustained Kenzan and Taste for the Exotic

Kenzan had created his own distinctive approach to presenting Chinese elements, through his work in underglaze iron oxide. He also worked from early on to create work inspired by the ceramics of other countries. His ceramics trade was directed at cultured individuals who treasured imported items from China, Southeast Asia, and Europe. Kenzan was himself the product of the same social environment, and he knew exactly what those individuals would like. In creating replicas, he was also carrying on a Kyoyaki, tradition of copying wares from other areas. It appears that his replicas were a major part of the Kenzan kiln`s production and a major source of its income.

In his replicas, we see Kenzan`s talent at work making effective use of the distinctive qualities of the original, his starting point, and then integrating elements from it into an innovative design.

Octagonal mukozuke with replica of Dutch floral design

in underglaze enamels

Ogata Kenzan Edo period (18th century)

Idemitsu Museum of Arts

Section4

A Universe in a Covered Box ― In a Vessel, Another World

Kenzan created vessels in a great variety of forms, including square plates and replicas, at the Narutaki kiln. The most distinctive are his covered boxes. The gentle, rounded forms of his boxes were inspired, it is believed, by baskets and lacquerware. Of particular note in his covered boxes is the monochromatic space in their interior, in contrast to their highly decorated exterior. It is as though one encounters another world revealed only upon lifting the box`s lid. These boxes open the doors to a separate world, detached from the every day, inviting us to as yet unknown experiences. Each of these covered boxes contains its own universe, a universe created by Kenzan.

Important Cultural Property

Covered box with pampas grass design

in underglaze blue and iron oxide,with gold

Ogata Kenzan Edo period (18th century)

Suntory Museum of Art

Important Cultural Property

Covered box with pine design in underglaze iron oxide,

underglaze blue, with gold, silver, and white

Ogata Kenzan Edo period (18th century)

Idemitsu Museum of Arts

Section5

The Colorful World of Kaiseki ― Freedom from the Vessel Form

In 1712, Kenzan moved his kiln and studio from Narutaki to central Kyoto(Nijo Chojiya-cho) and began creating many wares for serving kaiseki, tea ceremony meals. He had previously produced kaiseki wares in Narutaki, but the times had shifted. Now Kyoyaki as a whole was moving to mass production of vessels for serving food and drink. Kenzan boldly entered this highly competitive field.

His most powerful weapons in that fierce competition were his fresh new designs, based on concepts created by his older brother, Korin. Mukozuke dishes with designs bordering their rims or wide-mouthed bowls that capture the moment when a stream is racing along, transcending the boundary between the interior and exterior: even today, his ideas, cutting across between the three-dimensional and the flat, seem new and full of playful inspiration.

Kenzan achieved great success with his colorful, varied kaiseki wares, which were unconstrained by the conventions associated with the vessel form.

Mukozuke with Tatsuta River design in overglaze enamels

Ogata Kenzan Edo period (18th century)

Miho Museum

Mukozuke with chrysanthemum design in overglaze enamels

Ogata Kenzan Edo period (18th century)

The Gotoh Museum

Sauce server, spring grasses design in overglaze enamels

Ogata Kenzan Edo period (18th century)

Suntory Museum of Art

Section6

Kenzan, as Inherited and Passed on ― His Final Years and Unknown Edo Lineage

Kenzan moved to Edo in about 1731, entrusting his kiln in Kyoto to his adopted son, Ihachi. Ihachi apparently continued working energetically as a potter, but information about the kiln`s subsequent history is lacking. Kenzan`s lineage came to an end in Kyoto.

In Edo, however, a Kenzan revival occurred, half a century after his death, due to Sakai Hoitsu`s efforts to honor and keep alive the Rimpa school. Thanks to Hoitsu, a previously unidentified lineage of potters working in the Kenzan tradition was discovered in Edo, and Kenzan was positioned as a member of the Ogata branch of the Rimpa school. Hoitsu has given us a lineage of potters who continue what is regarded as the “Kenzan” tradition, from Miura Kenya to potters active in the modern period.

How did his successors understand Kenzan? Each had his own interpretation. For each of his heirs, Kenzan lives on as an inspiration.

Important Cultural Property

Box with Musashino and Sumida River design

Ogata Kenzan Edo period (1743)

The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2026 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31