- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

Confucianism in Japanese Art

November 27, 2024 to January 26, 2025

*Download the list of changes in works on display

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition.

The list of changes in worksPDF

*The order of chapters may change at the exhibition venue.

Section 1

Educating Rulers

According to the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters, Japan's oldest written record), the Analects was one of the Confucian classics transmitted to Japan from China at the start of the fourth century. Subsequently, Japan's rulers, including the emperor, aristocrats, and warriors, highly regarded the Confucian classics that arrived from China and always kept them by their sides to study “the frame of mind required by those who wanted to create an ideal world.”

It was in this context that the spaces inhabited by rulers in their palaces and castles were often decorated with art using Confucian themes imported from China. Because they were intended to promote virtue and suppress evil, these works are called moralistic or admonitory paintings.

Examples of these moralistic paintings, from as far back as the Heian period (794-1185), include The Chinese Sages (portraits of thirty-two wise ministers from ancient China) on screens placed behind the emperor’s throne, the most sacred spot in the Imperial Palace. Another example of paintings depicting images imported from China were portraits of the Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety. The Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety sliding door paintings, at Nanzen-ji Temple in Kyoto, were originally admonitory paintings created for the reception hall of Emperor Ōgimachi's retirement palace (the Ōgimachi-in Sentō Gosho) in 1586. The Illustrations of Exemplary Emperors, based on the collection of that title compiled during China's Ming dynasty, are also admonitory paintings depicting the exemplary good deeds and cautionary misdeeds of Chinese emperors throughout history. These subjects typically appear in paintings by members of the Kanō school and other prominent painters of the time, who had close relationships with the ruling class.

In this section, we focus on Confucian art introduced from China and the large-format admonitory art influenced by it that decorated rooms in the residences of emperors and shoguns. We bring these celebrated works together in one space to better appreciate their role in the education and mental preparation of Japan's rulers.

Kanō Takanobu, 8 of 20 panels, 1614, Ninna-ji Temple, Kyoto

【To be shown over an entire period (with panel change)】

Attributed to Kanō Eitoku, 8 of 14 panels, 1586, Nanzen-ji Temple, Kyoto

【To be shown over an entire period (with panel change)】

Kanō Tan'yū, 4 Fusuma panels (8 sides: front and back), 1634, Nagoya Castle office

【On display between Dec. 25 and Jan. 26】

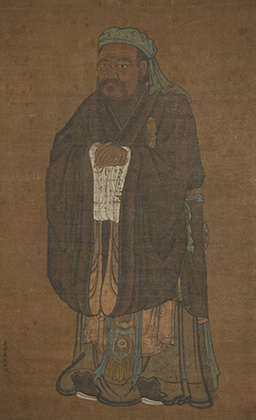

Attributed to Dai Jin, Hanging scroll

China Ming dynasty, 15th-17th century, Shibunkai

【On display between Nov. 27 and Dec. 23】

Section 2

Zen Priests and Confucianism

From the thirteenth century on, Zen priests were the brains behind the strong bonds between Japan's rulers and Confucianism. During this period, Zen priests not only brought back with them the latest Zen thinking from China. They were interested in the whole spectrum of Song learning, including the new trends in Confucianism that appeared during the Song. Besides Zhu Xi's Neo-Confucianism, these also included the idea that the three are one, since Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism shared the same origin. Familiar with the latest learning from China, these Zen priests devoted themselves to learning ever more and displayed the results in literature and paintings. In this part, we draw attention to the medieval-period connections between Zen priests and Confucianism through such works as Sesson Shūkei's Confucius Contemplating the Tilting Vessel (the Museum Yamato Bunkakan), which illustrate the results of their Confucian studies.

Ashikaga Gakkō (in what is now Ashikaga city, Tochigi prefecture) is famous for being Japan's oldest school. Founded in the medieval period and widely respected by Japan's Warring States period daimyo, it was a center for the study of Confucianism where for generations the headmasters were Zen priests. In this section, we introduce numerous precious items, starting with a National Treasure, the Commentary on the Book of History, an important Song dynasty document donated to the school by Uesugi Norizane, and including Zenguan on Governing, in a woodblock edition printed in moveable type that Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616) ordered the ninth Ashikaga Gakkō headmaster Kanshitsu Genkitsu (1548-1612) to produce, and Japan’s oldest extant sculpture of Confucius, created in 1535 during the Muromachi period, and enshrined at the Ashikaga Gakkō.

Sesson Shūkei, Hanging scroll

Muromachi period, 16th century, The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

【On display between Dec. 25 and Jan. 26】

Sculpture, 1535, Ashikaga School Historic Site Office

【To be shown over an entire period】

Section 3

Thinking that the Edo Bakufu Prioritized

As the curtain went up on the Edo period, reception of Confucianism changed dramatically. The Edo Bakufu (the Tokugawa shogunate) greatly valued the Confucian scholars Fujiwara Seika (1561-1619), from Zen Buddhist temples, and Hayashi Razan (1583-1657) to promote Zhu Xi's Neo-Confucianism to all social classes, from the rulers, the warrior class, to the commoner masses. Kanō Tan'yū and other Kanō school artists employed by the Bakufu produced numerous works reflecting this stance. Thus, for example, the phoenix, a Confucian symbol that an outstanding ruler had appeared, is frequently depicted in their art. It often appears in the works of subsequent generations of Kanō school artists after Tan'yū as well as in many craft objects.

Also, in 1632, the first-generation lord of the Owari domain, Tokugawa Yoshinao, supported Hayashi Razan's proposal to build a Confucius Temple at Hayashi's private residence in Shinobugaoka, in Ueno, northeastern Edo. In 1690, the Confucius Temple was moved by the fifth shogun, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, to Yushima, somewhat closer to the center of the city, where the following year what is now the Yushima Seidō Confucius Temple was built. In this section we show paintings and crafts associated with the history of the Yushima Seidō.

Kanō Tan'yū, Left screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens

Edo period, 17th century, Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between Dec. 25 and Jan. 26】

Kanō Tan'yū, Right screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens

Edo period, 17th century, Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between Dec. 25 and Jan. 26】

Section 4

Confucianism Permeates Japanese Culture

During the latter half of the Edo period, there were ample opportunities to learn about Confucianism, from lectures given by Confucian scholars to the common people to education for children. The descendants of Hayashi Razan successively inherited the position of "Daigaku no Kami" (Head of the Shōheizaka Gakumonjo [Shōheizaka Academy]) and provided education for the samurai. But it was also a feature of the Edo period that a steady stream of commoners appeared who devoted themselves to self-study of Confucianism. As Confucianism permeated mass culture, many artists reflected that thinking in ukiyo-e. Examples include woodblock prints on the five constant virtues by Suzuki Harunobu (1725?-1770) and the Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861).

Confucian thought was also incorporated into popular fiction such as the immensely popular Eight Dogs by Kyokutei Bakin (1767–1848), as well as Kabuki plays, including The Treasury of Loyal Retainers and Twenty-Four Japanese Paragons of Filial Piety. These in turn became subjects for new works of art. Additionally, everyday craft objects featured motifs like snow and bamboo shoots from the story of Meng Zong, one of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety, integrating these values into daily life.

In this final section, we introduce ukiyo-e, textiles and lacquerware from the early modern period on, illustrating how Confucian learning permeated everyday life.

Suzuki Harunobu, 1767, Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between Dec. 25 and Jan. 26】

(Tachibana in Roundel Crest)

Meiji-Shōwa periods, 19th-20th century, Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between Nov. 27 and Dec. 23】

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2024 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

2024 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31