- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

Tumultuous Times

―Painters in the Bakumatsu and Meiji

October 11 to December 3, 2023

*Download the list of changes in works on display

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition.

The list of changes in worksPDF

*The order of chapters may change at the exhibition venue.

Chapter 1

Late Edo (Bakumatsu)

Edo Painting Circles

In the 19th century, the capital city of Edo was a veritable cornucopia of pictorial creation as artists produced everything from ukiyo-e prints to Kanō school, Nanpin school, and literati paintings.

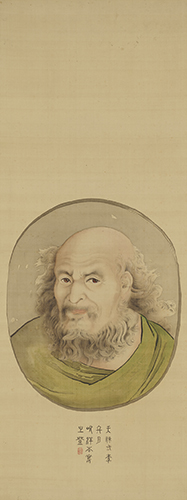

The painters of the Kanō school reigned supreme over Edo period painting circles. Beyond their preservation of the traditional funpon copy production method, they also incorporated painting methods and subjects from other schools, everything from yamato-e to ukiyo-e, the Rimpa school and Western painting techniques. Some of the painters who emerged from that training system went on to produce individualistic works that differed from existing Kanō school forms. Kanō Kazunobu (1816–63) first studied under Shijō school and Tosa school masters before entering training under the Kanō system. He added Western-influenced shading techniques to traditional Buddhist painting themes in order to produce his compelling, vividly colored Five Hundred Arhats hanging scrolls (Zōjōji, Tokyo).

Tani Bunchō (1763–1840) was a hugely influential painter in Edo painting circles who studied a wide range of painting styles and forms. In turn, his students went on to challenge themselves to create new forms of expression, unbound by painting school stylistic constraints. The Bunchō follower lineages extended into the Meiji period and later eras, with their styles in turn taken up and continued in 20th century and later Nihonga.

Focusing on these two major schools of painting in 19th century Edo, namely the Kanō school and Bunchō’s followers, this chapter introduces just a few of the myriad painters who worked in Edo’s painting circles during the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Kanō Kazunobu

1854–63 (Kaei 7–Bunkyū 3), Zōjōji, Tokyo

【To be shown over an entire period】

Kanō Kazunobu

1854–63 (Kaei 7–Bunkyū 3), Zōjōji, Tokyo

【To be shown over an entire period】

Watanabe Kazan

Hanging scroll, 1840 (Tenpō 11)

Kyushu National Museum

【On display between Nov. 8 and Dec. 3】

Chapter 2

Late Edo (Bakumatsu)

Western-influenced Painting

As we consider how art advanced from the pre-modern era to the modern in Japan, we cannot overlook the question of how Western painting was received and incorporated into the arts during that period. Information on Western painting was severely limited under the Tokugawa shogunate’s exclusionary policies. And yet, the Japanese people were able to learn about the outside world, from the arts to sciences, via what came to be known as Dutch studies (rangaku)—a catch-all term for what they could glean from the Dutch traders who were allowed into the port of Nagasaki and books written in Dutch. As part of this trend, Western-influenced-painting flourished during the mid-Edo period. In painting, Shiba Kōkan (1747–1818) and Aōdō Denzen (1748–1822) produced Western-influenced paintings (yōfūga) that incorporated painting methods from Europe. In the latter half of the Edo period, large numbers of imported copperplate prints and Western books flowed into Japanese society. Artists learned from these materials and produced various forms of Western-style paintings that incorporated shading and perspectival techniques.

In the late days of the Tokugawa shogunate, a Western-influenced painter named Yasuda Raishū (?–1859) was active in the capital of Edo. Raishū, who first studied under Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), excelled at intricate copperplate prints, and also painted works with a distinctive Western-influenced expression.

This Western-influenced painting did not spread as a school but rather can be seen as conveying how various Edo period painters turned towards and drew from Western painting. With a central core of Yasuda Raishū works, this chapter focuses on late Edo (bakumatsu) Western-influenced painting.

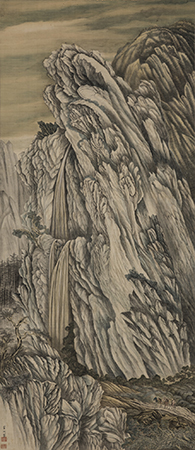

Yasuda Raishū

Hanging scroll, Edo period, 19th century

Masakichi Hirano Art Foundation

【On display between Nov. 8 and Dec. 3】

Haruki Nanmei

Hanging scroll, ca. 1851 (Kaei 4)

Kobe City Museum

【On display between Oct. 11 and Nov. 6】

Chapter 3

Late Edo (Bakumatsu)

Ukiyo-e

Earlier periods of ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings focused on images of actors and beautiful women, while the 19th century saw the development of new thematic genres. Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) brought landscape views of famous sites (meisho-e) and bird and flower subjects into vogue. Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861) had become famous for his warrior prints (musha-e), but also broke new ground through his satirical comic images and his exploitation of the wide-screen effect possible in woodblock print triptychs. These three giants of the field, Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Kuniyoshi, each trained numerous followers, with the Utagawa school becoming the dominant power in late Edo period ukiyo-e.

Ukiyo-e works were always created as a reflection of their own time and often took on a journalistic role. So too in the late Edo (bakumatsu) period. The arrival of Perry’s Black Ships, the opening of Yokohama’s international port to foreign ships, and other timely events became print subjects. Utagawa school artists created numerous images in the so-called Yokohama ukiyo-e form, works that depicted the Westernized customs and aspects of the new port town of Yokohama.

This chapter focuses on Utagawa Kuniyoshi and the Utagawa school artists as it introduces the multitude of richly varied ukiyo-e works created by late Edo (bakumatsu) period artists.

Utagawa Yoshitsuya

Ōban format polychrome woodblock print triptych

1860 (Man’en 1), Chiba City Museum of Art

【On display between Nov. 8 and Dec. 3】

Chapter 4

Painters in a Turbulent Age

In 1853 (Kaei 6), Perry’s Black Ships arrived in Japan. This set off a chain of dizzying changes, from the opening of the country to non-Japanese to the transfer of power from the Tokugawa shogun to the Meiji emperor, the collapse of the Tokugawa shogunal government, the Boshin War, and then the establishment of the new Meiji national government. In 1868 (Keiō 4), the name of the capital city was changed from Edo to Tokyo, and the imperial era name was changed to Meiji. Generally, it has been common to use this social transformation as a cut-off point, and then consider art before as separate from that after 1868. However, in recent years, scholars have emphasized the continuity between the Edo and Meiji periods as they reevaluated the painters and print artists of the late Edo (bakumatsu) to Meiji periods.

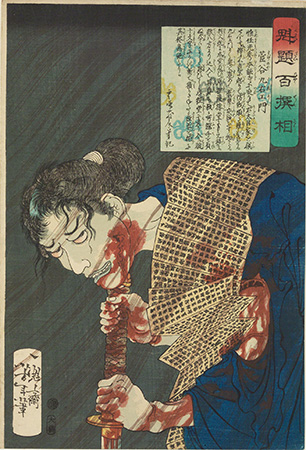

This chapter takes up the artists who were born in Edo under the Tokugawa shogunate and were then active in Tokyo under the Meiji government. Kikuchi Yōsai (1788–1878), the father of modern history painting. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–92), known for his shocking blood-stained pictures (chimidoro-e). Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831–89), the Demon of Painting (gaki) who challenged himself with myriad subjects. Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915), who dazzled the world with his luminous light prints (kōsenga). This chapter presents a gathering of their works that show how they continued Edo period pictorial traditions, all while conveying the sentiments of a new age.

This section also displays bunmei kaika nishiki-e, the woodblock genre that provides pictorial evidence of how Tokyo, as the epicenter of modern Japan, was swept up in the Westernization process called bunmei kaika, the Meiji government’s push to civilize (bunmei) and develop (kaika) the country.

Kawanabe Kyōsai

Pair of hanging scrolls, 1871–89 (Meiji 4–22)

Itabashi Art Museum

【On display between Oct. 11 and Nov. 6】

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Ōban format polychrome woodblock print, 1868 (Keiō 4)

Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts

【On display between Oct. 11 and Nov. 6】

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2026 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31