- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

A Mokubei Retrospective

February 8 to March 26, 2023

*Download the list of changes in works on display

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition.

*The period is subject to change.

The list of changes in worksPDF

Section 1: Mokubei, Literatus, Enjoys Creating Ceramics

Mokubei’s ceramics were inspired by antiquities from China, Korea, and Japan. He did not, however, stop at faithfully copying the external appearance of those ceramic works from the past. Based on his extensive knowledge of Chinese ceramics acquired from Chinese books and his own appreciative observation of antique wares, he extracted elements of shapes and motifs from a variety of those wares and recomposed them from his own point of view. That bold stance generated Mokubei’s ceramics, with their powerful individuality and wondrous fascination.

Starting in his teens, Mokubei learned seal carving from Kō Fuyō (1722-1784), a literatus of enormous prestige. He also enjoyed appreciating antique wares and, as a literary man himself, continued to train and engage in greater cultivation. He also began to engage in creating ceramics because he aspired to do so. He studied with Okuda Eisen (1753-1811) and worked hard along with Kyoto potters who were his contemporaries (Kinkodō Kamesuke, Ninnami Dōhachi). In his thirties, encountering Ceramics Explained (陶説), a book by a Qing period Chinese author, and working to reprint it encouraged and nourished his work in ceramics. He then was given the position of ceramics master by appointment to Prince Shōren-in in Awata, Kyoto, and exercised his extraordinary abilities as a superb craftsman in that role.

This section introduces ceramics in which Mokubei, applying his unique point of view, freely blended elements of vintage ceramics of a great variety, unbound by convention. Their forms, colors, motifs, and, at times, the inscriptions on their boxes, express Mokubei’s sense of play, as a literary man, and his individuality, which we hope you will enjoy experiencing.

Mokubei, Edo period, 19th century

Tokyo National Museum

【To be shown over an entire period】

Image: TNM Image Archives

Mokubei, 1809

Private Collection

【To be shown over an entire period】

Mokubei, 1807-08

Suntory Museum of Art

【To be shown over an entire period】

Section 2: Mokubei, Literatus, Loves Sencha

This section features Mokubei’s sencha tea utensils. Sencha, a type of green leaf tea, was strongly associated in Japan with embracing Chinese literati lifestyles and ideals. In the mid eighteenth century, a Zen priest, Baisaō (1675-1763), “the old tea seller,” carrying sencha tea utensils, launched a mobile tea stall, moving it between his choice of scenic locations inside and outside Kyoto. There he would encourage passersby to sip a cup of sencha. Baisaō’s way of life, turning his back on the secular world, was a significant influence on the literati of Mokubei’s generation. Sencha was also strongly tied to creating poetry, calligraphy, and paintings, all means of self-expression among literati, and to settings for appreciating them. Enjoyment of sencha spread widely, especially in Kyoto and Osaka, regardless of participants’ social status. The sencha way of tea then became established as an art in itself.

Amidst the flourishing of sencha, Mokubei had begun creating ryōro (ceramic braziers), kyūsu (teapots), sencha tea bowls, and other sencha utensils. By his thirties, they had earned great acclaim. In, for example, the Sencha Hayashinan (Quick guide to sencha, 1802), Mokubei’s sencha utensils were evaluated as “Skillful copies of Chinese works,” giving us a glimpse of his renown.

Mokubei’s playful spirit in adapting ideas and styles found in older works, particularly Chinese ceramics, was displayed to the full in his sencha utensils. That playfulness is particularly striking in, for example, the utensils he created for Tanaka Kakuō (1782-1848), the founder of the Kagetsuan school of sencha. The remarkably literary ryōro braziers and sencha tea bowls, bearing poems with tea as their subject from Tang and Song period China densely inscribed on their surfaces, fascinate with their strong expression of the individuality of Mokubei, who loved sencha himself.

Mokubei, 1824

Private Collection

【To be shown over an entire period】

Mokubei ,Edo period, 19th century

Aizu Museum, Waseda University (Tomioka Shigenori Collection)

【To be shown over an entire period】

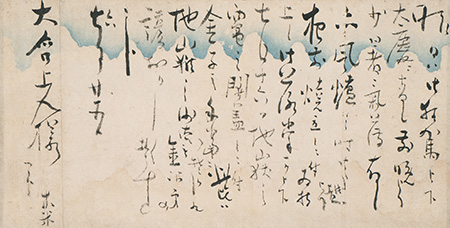

Section 3: Mokubei, Literatus, and His Delightful Friends

This section deeply explores the fascination of Mokubei the literatus from the perspective of his friends and acquaintances. For example, his close friend Tanomura Chikuden (1777-1835), a painter, stated, it is said, “Mokubei’s stories were of immeasurable depth. Mokubei loved joking, and when I was talking with him, if I thought he had laughed, he was persuading, if I thought it was true, it was a lie” (Record of Paintings of Chikudensō Teachers and Friends). The magnificent last words he uttered to Chikuden may have expressed Mokubei’s deep attachment to his work in ceramics and his pride as a literatus, in a flippant manner.

Chikuden was not an exception. Mokubei’s friends in his late years included the Confucian scholar Rai Sanyō (1780-1832), the Buddhist priest Unge (1773-1850), and the practitioner of Western medicine Koishi Genzui (1784-1849), all among the respected literati of their day. Among these rather younger men, Mokubei, who was known as the “literate potter,” was erudite and filled with intellectual humor; he was regarded by them with a warmly respectful gaze.

The exhibits in this section focus on letters Mokubei wrote to dear friends, works from his collection characteristic of his art name Kokikan (“an eye for old vessels”), and materials related to the literati from whom he had received training before he made his name as a ceramic artist. The image of Mokubei that takes shape through considering those friendships is endlessly fascinating today.

Tanomura Chikuden, 1 hanging scroll,1823

Private Collection

【On display between Feb. 8 and Feb. 27】

Mokubei, 1 hanging scroll, Edo period, 19th century

Private Collection

【On display between Mar. 1 and Mar. 26】

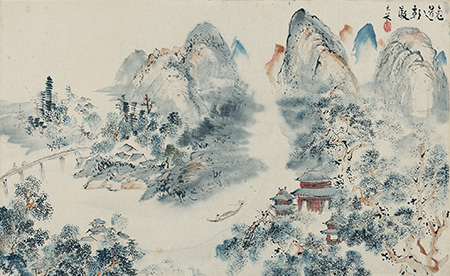

Section 4: Mokubei, Literatus, Enjoys Painting

Mokubei had had an interest in painting, as one of the elements of Chinese cultured activity, from his youth. Of the works for which a date of production can be determined, most are from the latter half of his fifties on. Nearing the end of his life, Mokubei broadened the scope of his creative activities in the context of his stimulating interactions with literati who gathered in Kyoto, regardless of their social status or age. One can imagine him becoming newly aware of his way of life as a literatus who had mastered a variety of arts.

The distinctive features of Mokubei’s paintings are that the majority had landscapes as their subject and, above all, that many were tamegaki, paintings with an inscription stating that they painted at the request of a specific person. His tamegaki works resemble private letters from Mokubei to their recipient. One of the ways to enjoy Mokubei’s paintings is to think about Mokubei’s humanity, through his paintings. For example, looking at one of his landscapes, which are rather sombre yet somehow have a sense of transparency, one senses Mokubei’s complex character.

This section presents landscape paintings extant from Mokubei’s earliest periods, gloriously calm landscapes based on the actual scenes in Uji, tea’s sacred territory, and other masterworks, including rare paintings of botanical subjects and Buddhist paintings. Through them, we unravel the compelling nature of Mokubei’s paintings, beloved by many literati.

Mokubei, 1 hanging scroll, Edo period, 19th century

Private Collection

【On display between Mar. 1 and Mar. 26】

Mokubei, 1 hanging scroll, 1826

Wakimura Scholarship Foundation

【On display between Feb. 8 and Feb. 27】

Mokubei, 1 hanging scroll,1829

Private Collection

【On display between Mar. 1 and Mar. 26】

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2024 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

2024 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31