- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

Suntory Museum of Art 60th Anniversary Exhibition

Masterpieces from the Japanese painting collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art

April 14 to June 27, 2021

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition.

*Download the list of changes in works on display

*Photography is permitted at this exhibition.

*This exhibition will travel to Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art (July 8 to September 5, 2021: TBD) and MIHO MUSEUM (September 18 to December 12, 2021: TBD).

*Temporarily closed from Apr. 25 to May 31 as precaution against COVID-19.

The list of changes in worksPDF

Chapter 1 Ink Painting

Ink paintings are created in sumi ink, which can easily be adjusted to produce gradations of lightness and darkness to express the subject’s volume, distance, lighting, and state of the atmosphere. Ink painting dates back to eighth-century China in the Tang period (618-907) and was first introduced to Japan in the Nara period (710-794). Later, during the Kamakura period (1185-1333), with trade between Japan and China booming, Zen culture flourished. Zen priests from China came to Japan, serving at temples in Kamakura and Kyoto and bringing many ink paintings with them. The passion for ink painting continued unabated, with the Ashikaga shoguns of the Muromachi period (1336-1573) accumulating many superb paintings. The Tokugawa shoguns (1603-1868) inherited that aesthetic culture, in which the styles of Chinese paintings from the Southern Song (1127-1279) and the Yuan periods (1271-1368) were the mainstays of Japanese painting from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries. This section introduces the world of ink paintings, a world also cherished in America, with the focus on artists active in the sixteenth century, Japan’s Warring States period.

Left screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens, Muromachi period, 16th century,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of funds from Mr. and Mrs. Richard P. Gale

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Right screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens, Muromachi period, 16th century,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of funds from Mr. and Mrs. Richard P. Gale

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

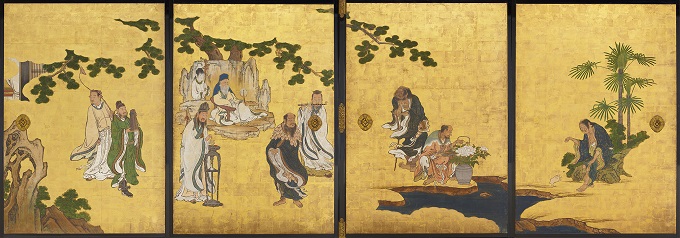

Chapter 2 The Age of the Kano School

The Kano school was a group of professional painters centered on the Kano clan, members of which were linked by blood ties. It developed, under the patronage of those in power, from the Muromachi period (1336-1573) on. In the Edo period (1603-1868), when the center of government had shifted to Edo, the main Kano family also moved its base from Kyoto to Edo. Kano Tan’yū (1602-74), grandson of Kano Eitoku (1543-90), became a painter by appointment to the Edo shogunate and carried out a stylistic revolution in the Kano school with his shōsha tanrei, elegant and refreshing, style. The Kano school continued to serve as official artists to the shogunate and many domains throughout the Edo period and was the dominant school in the art world. While Tan’yū moved to Edo, Eitoku’s pupil Kano Sanraku (1559-1635), his adopted son Kano Sansetsu (1590-1651), and their line remained in Kyoto, where they created individualistic works that differed from the Tan’yū style. This section is devoted to exploring the achievements of the Kano school through works by Tan’yū, Sanraku, and other artists.

Four sliding doors, Edo period, 1646,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, The Putnam Dana McMillan Fund

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Eight-panel folding screen, Edo period, 1663,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of the Clark Center for Japanese Art & Culture

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Chapter 3 Yamato-e: Seasonal Themes and Narrative Painting

In the Heian period, starting in the late ninth century, consciousness of “Yamato” (Japan) versus “Kara” (China) was the context in which Yamato-e, paintings with Japanese manners and customs and things Japanese as their themes, emerged. Yamato-e thus initially meant paintings on Japanese, rather than Chinese, themes, but developed over time into a distinctively Japanese painting style. In the latter half of the thirteenth century, Chinese paintings from the Southern Song (1127-1279) were widely received in Japan, and they came to be called Kara-e, Chinese paintings, while all of what had been traditional Japanese paintings were labelled Yamato-e. In contrast to Kara-e, which were mainly ink paintings, Yamato-e were characterized by decorativeness and rich use of color and can be divided broadly into large format paintings (sliding door and folding screen paintings, for example) of subject such as scenes of the four seasons and small paintings, usually narrative paintings with themes taken from The Tale of Genji and other classics of Japanese literature. The Yamato-e in the Minneapolis Institute of Art collection include many superb folding screen paintings.

Left screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens, Edo period, 17th century,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Right screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens, Edo period, 17th century,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Chapter 4 Rinpa Tradition

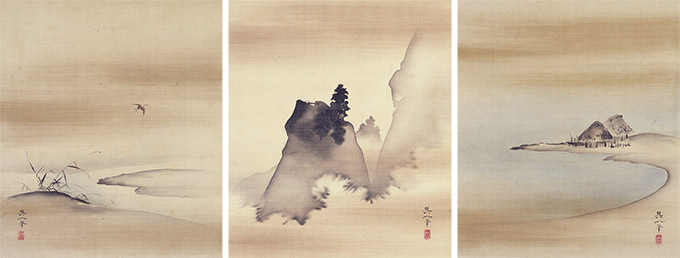

The Rinpa tradition began with Tawaraya Sōtatsu (n.d.), who was active in the early seventeenth century. In a period in which the culture of the imperial court was being revived in Kyoto, Sōtatsu, who created decorative papers for calligraphy, among other works, created stylized versions of motifs extracted from traditional works, developing a distinctive style that made effective use of the tarashikomi technique of creating pooled, blurred ink or colors. Ogata Kōrin (1658-1716) admired and carried on Sōtatsu’s style. Then Sakai Hōitsu developed his own characteristically Edo style infused with the wit of haikai poetry. His students went on to form the Edo Rinpa tradition (its name derived from the “rin” in Kōrin’s name and “ha,” meaning tradition). This section focuses on works by Sōtatsu, Hōitsu, and Hōitsu’s leading student, Suzuki Kiitsu (1796-1858), in exploring the beauty of Rinpa-style art, which epitomizes Japanese paintings.

Triptych of hanging scrolls, Edo period, 19th century,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Elizabeth and Willard Clark

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

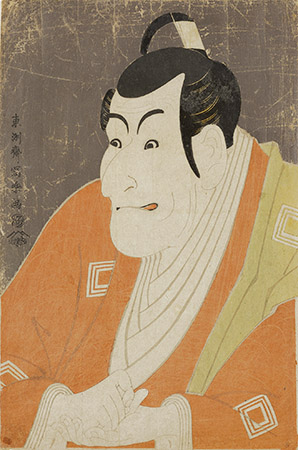

Chapter 5 Ukiyo-e Prints and Paintings

During the Edo period (1603-1868), the city of Edo developed into a huge metropolis. There a distinctive new art form, the ukiyo-e print, bloomed. Hishikawa Moronobu (1618?-94) is regarded as the father of the ukiyo-e, pictures of the floating world (the fleeting pleasures of life). With an organized market and a publisher-centric division of labor between the ukiyo-e artist, block carver, and printer, the ukiyo-e became Edo’s iconic art form. Because the earliest publishers located themselves in the Nihonbashi district, in the very heart of Edo, prints came to be sought by travelers from the provinces as well as townspeople. The ukiyo-e print evolved from black-and-white prints to the polychrome prints known as “brocade prints” (nishiki-e). In the mid-nineteenth century, when many famous ukiyo-e artists were active, there were more than 260 publishers producing ukiyo-e. This section presents a selection of celebrated prints from the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s ukiyo-e collection.

Woodblock print (nishiki-e), Edo period, 1794,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Bequest of Richard P. Gale

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display between May 26 and June 27】

Woodblock print (nishiki-e), Edo period, 1830–33,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Louis W. Hill, Jr.

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display between Apr. 14 and May 24】

Chapter 6 Japanese Literati Painting (Nanga)

Japanese literati painting, or Nanga, was a new mode of painting produced, from the mid-Edo period onwards, by those fascinated by the Chinese literati and Ming and Qing period Chinese paintings. A trend was growing to create paintings with a sense of free creativity, in contrast to the works of the Kano school, which then dominated the world of painting. The introduction of Ōbaku Zen sect and the spread of Confucianism and Chinese poetry and prose brought a growing appreciation for Chinese culture across a broad segment of society. Ink paintings of utopias in the Chinese manner and realistic depictions of landscapes, filled with the excitement of having actually seen them, were among the fascinating paintings were created. A distinctively Japanese version of literati painting (Nanga) spread to all parts of Japan, from the Tōhoku to Kyūshū, creating a new dimension in the history of Edo-period painting.

Left screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens, Edo period, 1821,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary And Jackson Burke Foundation

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Right screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens, Edo period, 1821,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary And Jackson Burke Foundation

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Chapter 7 Innovators of the Art Scene

The latter half of the Edo period saw the rise of painters creating literati (Nanga) or naturalist paintings unbound by existing schools and styles. Among them, the artists known as the “eccentrics”, notably Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800) and Soga Shōhaku (1730-81), broke new ground, creating ink paintings with radically deformed compositions and detailed paintings in strong colors. At one time, their work was not highly regarded, but American and other lovers of Japanese art who resided outside the country acquired many superb works by these artists, preventing their paintings’ being scattered and lost. This section of the exhibition also introduces works by the Nagasaki school, who were influenced by both Chinese and Western painting and created a diverse group paintings. Enjoy examining the daring efforts of artists who revolutionized the world of painting in the Edo period.

Left screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens, Edo period, 18th century,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Elizabeth and Willard Clark

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Right screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens, Edo period, 18th century,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Elizabeth and Willard Clark

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Chapter 8 From Late Edo to the Modern Period

In the Meiji period (1868-1912), under the influence of the West, painting in Japan underwent major changes. New categories were born: Nihonga, “Japanese-style painting,” which carries on traditional methods inherited from various painting schools, and Yōga, “Western-style painting,” which uses Western techniques such as those applied in oil paintings and watercolors. The Shin Hanga, “new print,” and Sōsaku Hanga, “creative print,” both based on ukiyo-e, were among the diverse developments in modern art in Japan. Collections of modern art in Europe and America include little Japanese art, but the Minneapolis Institute of Art collection includes works by Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831-89), Watanabe Seitei (1852-1918), and Kano Hōgai (1828-88), Japanese artists highly regarded in the West. The collection is also distinguished by its inclusion of many Bijinga, paintings of beautiful women and Shin Hanga, both connected to the history of ukiyo-e. This exhibition also introduces the America-specific work of Aoki Toshio (1854-1912), who moved to the United States in the early Meiji period.

Hanging scroll, Meiji period, 19th century,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Elizabeth and Willard Clark

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2026 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31