- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

Reopening Celebration I

ART in LIFE, LIFE and BEAUTY

July 22 to September 13, 2020

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition

*Download the list of changes in works on display

*Photography is permitted at this exhibition, except for some works.

The list of changes in worksPDF

Chapter 1, Section 1:

Dressing: Make-up tools, and The Accessory Box with Fusenryo Design in Mother-of-Pearl and Maki-e Sprinkled Gold Decoration

Yosou is an old Japanese word that was used to mean “to groom” or “to decorate”. In various parts of our everyday lives, we dress and curate our outward appearances and at the same time arrange our inner selves: yosou encapsulates this aspect of humanity.

A survey of the history of art in Japan reveals that special attention was given to the intricate design of objects that, while used in daily life, exceeded practical considerations.

Of such tools, this section will focus in particular on make-up tools and hair decorations from the Heian (794-1185) to the Meiji period (1868-1912). We begin with the Accessory box with fusenryo design in mother-of-pearl and maki-e sprinkled gold decoration (a National Treasure), and consider decorated mirror cases, incense storage boxes, rouge containers, combs, and single and double-pronged hairpins, all created with a variety of materials and techniques. By tracing the changes in designs of great beauty that adorned the material of everyday life, aspects of the Japanese aesthetic can emerge.

Kamakura period, 13th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Edo period, Early 18th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Chapter 1, Section 2:

Dressing: Pictures of Beauties, and Kimono

Bijin-ga (“pictures of beautiful women”) and kimono are genres that reveal the sensibilities of everyday beauty and the fashions of the various times during which they were made. This is a theme that is central to the concept of our museum, “Art in Life”. During the Edo period (1603-1868) in particular, the merchant class, who held great economic power, enjoyed adorning their clothing in unconventional ways and from this adornment developed new and popular fashions. The kosode (a kimono with short sleeves) robe that is today common to Japanese clothing is based on the clothing trends of that time, which spread from the upper classes to the townspeople. There were also a great many books published that showcased templates for the designs that decorated these robes. Meanwhile, previous to the Edo period, women generally wore their hair down, but from that time onward a vast variety of tied-up styles – numbering in the hundreds – became popular.

We are also able to gauge the changes in fashions from bijin-ga portraits of women. Bijin-ga came to be made from the Kanbun era onward (1661-73), developing out of the so-called Kanbun bijin-zu or “images of Kanbun beauties.” Which were turned out in great numbers by painters. Bijin-ga become important examples of ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Women could access knowledge of the latest fashions from these pictures and they served as pictorial reference points for trends in clothing, hairstyles, and make-up.

With the introduction of western culture to Japan in the Meiji period came big changes in women’s fashions. Women began to use western accessories and wear western clothing, and the sokuhatsu chignon hairstyle was inspired by western ways of dressing the hair. Such changes can be observed in the woodblock prints of the time. On the other hand, there was a nostalgic attraction to pre-Edo styles. These too spread, and a great many pictures of women in retro clothing were created as well. This trend continued into the modern period, and is represented well in the works of Kaburaki Kiyokata.

This section introduces bijin-ga from the Edo period to the modern period along with paintings and woodblock prints that showed make-up and hairstyling techniques, brightly colored kosode robes and brocade uchikake kimono. Through pattern and design books, it also traces the transitions in these elaborate fashions. We also focus on the Tagasode, or “Whose Sleeves?” This painting itself was done on folding screens, and depicted clothing draped over yet other folding screens or stands. Employing real furniture, we try to convey the worldview captured within these paintings.

Left screen of pair of six-panel folding screens, Edo period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Yamamoto Taro, Three-panel folding screen, 2017

photo: by Yu Kusanagi

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Edo period, Latter half of 18th century-19th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between Jul. 22 and Aug. 17】

One of six panels, Edo period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Chapter 1, Section 3:

Dressing: Fitted Out for Battle with Armor and Helmets

It was not only women that adorned themselves; for the male military class it was also held to be extremely important. It can even be surmised that military gear was the garb of festivity and sacred ritual. The Koatsumori picture scroll reveals this, while The Tale of the Heike vividly narrates the splendid appearance of the Minamoto and Taira clans as they went into battle. From the latter half of the sixteenth century when guns were introduced to Japan, a change in forms of warfare from dueling to group gunfights can be observed; armor and military gear also gradually changed. The warrior class’s aim was to unify the realm and they designed their armor and helmets accordingly: the designs of the jinbaori coats and flags, saddlery and sword fittings are infused with their convictions and spirits. In each and every piece of weaponry and military gear that has been passed down through the ages is found a combination of the various advanced craft techniques of its period, from metalwork to lacquering and dyeing. Even if the function of the equipment was the priority in terms of manufacture, even today the sensitivity of the fine details and the novel designs draw the eye.

In this section, we present the aesthetic sense of the samurai who dressed in beautiful armor and used saddles decorated with bold motifs of spider and conch shells. Such an aesthetic could fairly be called “dandyism.”

Momoyama period, 16-17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Fukami Sueharu

1996

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Chapter 2, Section 1:

Celebratory Festivities and Banquets: the Furnishings of Celebration

The Suntory Museum of Art collection includes a vast number of pieces that were used at celebratory occasions and rites-of-passage such as births, coming-of-age ceremonies, and weddings. Special vessels and folding screens were ornamented with auspicious motifs, particular furnishings were brought out, and the site of celebration was decorated. There were also ceremonial Shinto-centered events such as Kamono kurabe uma horse racing and the Kyoto-based Gion Festival, along with annual seasonal events: the New Year festivities, the Girls’ Festival (Hina matsuri) and the Boys’ Festival (Tango no sekku). Paintings and woodblock prints that take these events as their subject were amply produced. These works clearly relay to us the importance that the festivities held in the everyday lives of people.

In this section, we can attain an idea of the elation experienced and expressed by people on these festive days through the artistic works that used horseracing and the Gion Festival as their subjects; folding screens used at weddings; vessels used at celebrations; and lacquerware scattered with auspicious motifs.

Kano Tan’yu, Right screen of pair of six-panel folding screens, Edo period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between Jul. 22 and Aug. 17】

Late Edo-Early Meiji period, 19th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Shibata Zeshin, Meiji period, 19th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Chapter 2, Section 2:

Festivals and Banquets: Folding Screens and Drinking Cups for Banquets

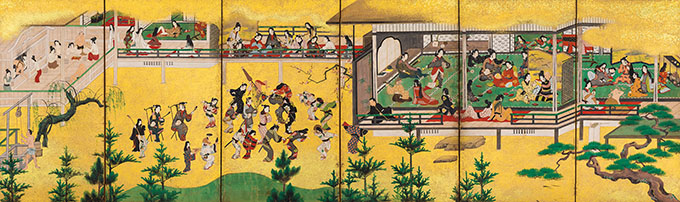

The banquet is a good example of celebration in daily life. We can directly sense the enjoyment and excitement of participants from the Yurakuzu (Merrymaking at a Mansion) painting, in which a banquet is depicted in detail. Dance, music, and games are all shown, and the ingenuity of the ways in which people enlivened the party comes across vividly to the modern-day viewer.

In the past as today, alcohol was an indispensable component of a party. By viewing each of the variety of cups available, the luxury of the tableware, and the creativity that went into making these, it is easy to imagine the way that people at banquets enjoyed the intriguing appearance and the beauty of sake cups - as well as their drinking.

Here, along with folding screens and hanging scrolls that portray the bright party environment, we can view sake vessels, the craft techniques required to produce them, and their materials: lacquer, ceramic, and glassware. The folding screen entitled Ueno hanami kabuki zu byobu (Cherry Blossom Viewing in Ueno: Kabuki Performance) brings together sake cups, tableware, musical instruments and tobacco trays to provide for us a reconstruction of the lively atmosphere of the banquets of the time.

Six-panel folding screen, Edo period, 1624-44

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between Aug. 19 and Sep. 13】

Edo period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Edo period, 19th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between Aug. 19 and Sep. 13】

Chapter 3, Section 1:

Foreign Tastes: Folding Screens of the “Southern Barbarians” and Early Western-Style Art

During the Momoyama period (1573-1615), an art was born of the exchanges between Japan Portugal and Spain and this art is one of the pillars of the Suntory Museum of Art’s collection. The Portuguese and Spanish came to Japan motivated by the opportunities offered by trade and a population that might be converted to Christianity. These so-called “Southern Barbarians” (Namban) became an object of curiosity and folding screens painted with portrayals of them became a popular form of art known as Namban byobu.

Namban byobu are paintings that show the ships of the foreigners that had drawn into the ports of Japan from far-off places, with their unloading of luggage of unusual objects and animals, and the disembarkation of the captain and his procession. It also depicted how Portuguese and Spanish spend their time in their own countries. They were rendered in Japanese style and its traditional techniques, and a large number of variations developed.

Jesuit missionaries set up seminaries at which instruction in language, music, and art was offered. “Western-style” painting in its early stages was done by artists who had learned the techniques of perspective and shading in these seminaries. It was not only icons used in worship that were produced, but also secular subjects such as European royalty, rural scenery, and maps of cities and of the world. Representative of the early period of this kind of art is the Taisei oko kiba zu byobu (Western Kings on Horseback) folding screen, the style of which was informed by copperplate engraving.

This section offers the pleasures of the essence of Namban art through folding screens and famous works from its early period.

Attributed to Kano Sanraku, Right screen of pair of six-panel folding screens, Momoyama period, Early 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between Jul. 22 and Aug. 17】

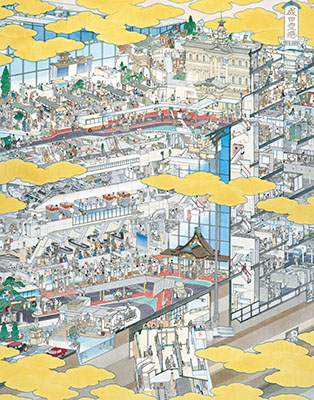

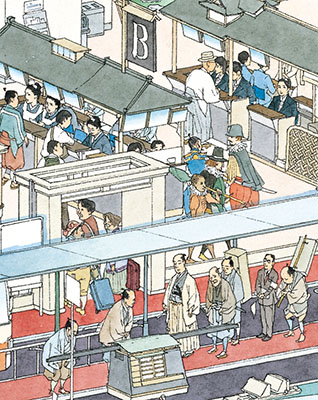

Yamaguchi Akira, 2018, Mizuma Art Gallery

©︎YAMAGUCHI Akira, Courtesy of Mizuma Art Gallery

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Yamaguchi Akira, 2018, Mizuma Art Gallery

©︎YAMAGUCHI Akira, Courtesy of Mizuma Art Gallery

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Pair of four-panel folding screens, Momoyama-Early Edo period, Early 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Chapter 3, Section 2:

Foreign Taste: Foreign Designs

With the beginnings of exchange with westerners in the latter half of the sixteenth century came not only influence in the form of new painting subjects but also developments in lacquerware. Lacquerware pieces were produced to please foreign tastes and these were dubbed Namban shikki. The highly-glossed black surfaces decorated with applied gold and mother-of-pearl were attractive to the foreign eye and were made into retables and communion pyxides, as well as cabinets and chests. A substantial amount of lacquerware was commissioned from the Japanese and shipped back to the home countries of the foreigners.

On the other hand, within Japan, foreign culture and its artifacts were considered to be at the cutting edge of design by the Japanese. Karuta – a card game from Portugal – was popular, and Namban people themselves were depicted as if they were gods of good fortune; an interest in Namban and other foreign cultures enjoyed broad popularity. Even the lacquerware produced for the Japanese market bore foreign patterns such as Southeast Asian stripes, Korean peony arabesques, and Chinese “sunken gold” and mother-of-pearl techniques. Lacquerware headed for other countries displayed a variety of East Asian expressions and elements.

Here, through the foreign tastes reflected in folding screens and lacquerware, we see the deliberate and thorough absorption of a new foreign culture that elevated the beauty of everyday life, and can sense the flexible mentality and vigorous curiosity of the Japanese of the time.

Edo period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display throughout the exhibition period】

Edo period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【On display between Jul. 22 and Aug. 17】

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2026 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31