- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

The 50th anniversary of the Suntory Foundation for the Arts

Styles of Play: The History of Merrymaking in Art

June 26 to August 18, 2019

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition

*Download the list of changes in works on display

The list of changes in worksPDF

1. The World of “Customs, Month by Month”:

Play as Part of Life

Paintings on the “month by month” theme, depicting events and customs throughout the twelve months of the year, were a major part of Yamato-e painting. Works following tradition in treating that subject allow us to discover the many traditional amusements that are still practiced today in Japan. They also vividly depict people at play throughout the seasons, enjoying parties, and cherishing the changing seasons: people playing battledore and shuttlecock, romping in the snow, admiring the cherry blossoms or the autumn moon. We can almost hear the children’s innocent shouts and the timbre of the music played during lively festivals.

Momoyama period, 16th-17th century

【To be shown between Jun.26 and Jul.22】

2. The Origins of Enjoyment:

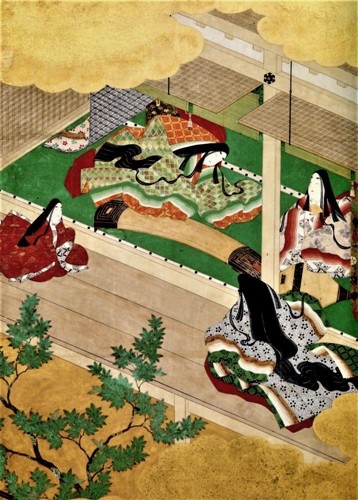

Cultivated Pleasures to Relish with All Five Senses

Examining the forms of play traditional to Japan, we find that many have their sources in the elegant pleasures enjoyed by Heian-period aristocrats. Playing music on the koto or biwa, competing at shellmatching games, keeping caged birds and vying over whose birds sang more beautifully, distinguishing two or more types of incense and guessing their names (the incense-matching game), playing kemari (a type of football) or competing with toy bows and arrows, even playing a form of polo: those aristocrats knew how to have fun. Think of the Tale of Genji, and scenes of its characters critiquing paintings in an art competition or playing kemari come to mind. Each of these amusements involves skills that require polishing the five senses, including hearing and the sense of smell, and refining one’s sensibilities. Some also provided stimulation through classic forms of training aimed at enhancing performance in the martial arts.

Six-panel folding screen (detail)

Edo period, 17th century, Suntory Museum of Art

【To be shown between Jun.26 and Jul.22】

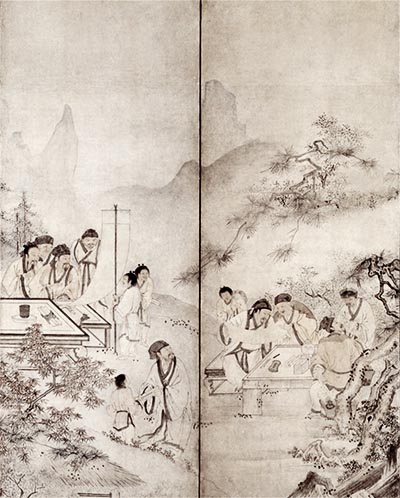

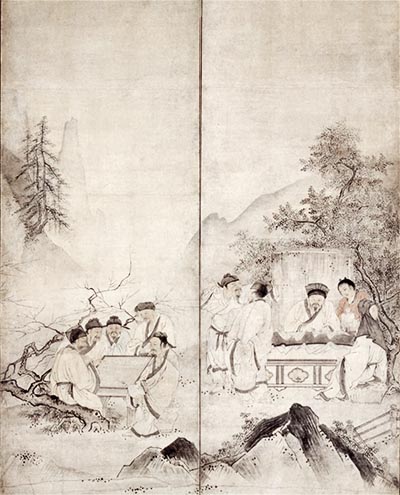

3. The Four Arts:

A Tradition of Aristocratic Taste

In China, playing the kin (a stringed instrument) and Go and practicing calligraphy and painting were known as the Four Arts and were regarded as expressions of aristocratic taste. The Four Arts also became an influential painting subject in Japan. As a part of Japanese culture from the middle ages on, the Four Arts were a favorite theme for fusuma (sliding door) and folding screen paintings decorating castles. Those paintings were produced in large numbers by every school of painting, but their content changed over time. In the “house of pleasure” paintings fashionable in the first half of the Edo period, the kin has been replaced by the shamisen and Go by sugoroku, another board game, but the elegance of China’s Four Arts has been deliberately incorporated in those paintings. The Four Arts subject lived on as the framework for parody pictures or visual allusions in which contemporary customs are likened to traditional ones.

Shabaku, Left screen of pair of six-panel folding screens (detail)

Muromachi period, 16th century, Private Collection

【To be shown between Jun.26 and Jul.22】

Shabaku, Right screen of pair of six-panel folding screens (detail)

Muromachi period, 16th century, Private Collection

【To be shown between Jun.26 and Jul.22】

4. The Genealogy of “Merrymaking” in Art (1) :

“House of Pleasure” Paintings

“House of pleasure” folding screens are works seeking to depict, compactly, every known form of pleasure, occurring from the depths of gardens to the inner spaces of residences, covering every corner of the picture plane. From people engaged in round dancing in the garden or boating on a pond to drinking sake or tea in a sitting room or smacking their lips over the savory treats being served, these screen paintings allocate space for every sort of amusements. The patterns on the men’s and women’s clothing are, of course, depicted gorgeously, and their expressions and gestures as they are absorbed in all these forms of play—including playing karuta, Japanese card games, sugoroku (a backgammon-like board game), dancing, or kemari football—are also carefully depicted. These “house of pleasure” folding screens were like large albums of samples of each type of amusement. Unfold the screen and one could forget the everyday gloom and, without moving at all, immerse oneself in a sense of relaxation to one’s heart’s content. In effect, these paintings functioned as personal simulation devices.

Left screen of pair of eight-panel folding screens

Edo period, 17th century

The Tokugawa Art Museum

© The Tokugawa Art Museum Image Archives / DNPartcom

【To be shown between Jun.26 and Jul.15】

Left screen of pair of eight-panel folding screens (detail)

Edo period, 17th century

The Tokugawa Art Museum

© The Tokugawa Art Museum Image Archives / DNPartcom

【To be shown between Jun.26 and Jul.15】

Six-panel folding screen (detail)

Edo period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【To be shown over an entire period】

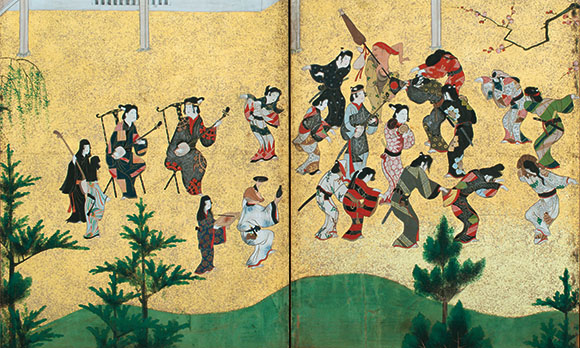

5. The Genealogy of “Merrymaking” in Art (2) :

Outdoor Amusements and Festivals

“Scenes in and around Kyoto” paintings exemplify a tradition of painting the bustling streets of the city and outdoor amusements that continued from the middle ages on. The “merrymaking under the cherry trees” folding screens popular in the Momoyama period are brimming with a sense of freedom, as people, dressed as gorgeously as they please, dance under cherry trees in full bloom.

In the Edo period, “scenes along the riverside at Shijo, Kyoto” were popular topics for both folding screens and picture scrolls. They depicted onna kabuki, theaters presenting puppet opera and other dramatic forms, people who have gathered to watch spectacles such as displays of rare animals, and people having fun with water play along the banks of the Kamo River in the summer’s heat.

With the transition from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern period, as the Edo-period bakuhan system of rule by the Tokugawa shogunate and individual domains stabilized, the presentation of merrymaking in art changed: from outdoor amusements to restricted areas and to interiors, from the masses to small groups of people of a certain class. Nonetheless, that period also saw the creation of works depicting people who have gathered to take part in outdoor festivals such as the Gion festival or horse racing at the Kamo Shrine. Those paintings give us a sense of how people played and had fun in the Edo period.

Right screen of pair of two-panel folding screens

Edo period, 17th century

SEIKADO BUNKO ART MUSEUM

©Seikado Bunko Art Museum Image Archives / DNPartcom

【To be shown between Jul.24 and Aug.18】

6. The Cultural History of Sugoroku:

Western-style Sugoroku Boards, Board Sugoroku, Picture Sugoroku

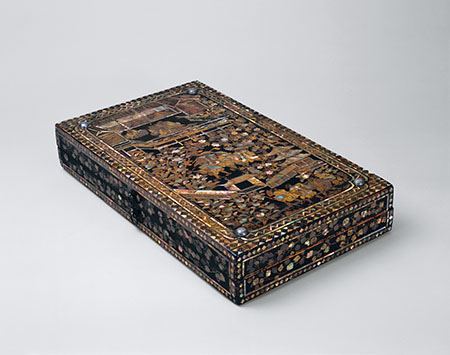

The Western-style Sugoroku Game Board with Kiyomizu-dera Temple and Sumiyoshi-taisha Shrine Design in Inlaid Mother of Pearl and Maki-e (Important Cultural Property; Suntory Museum of Art) is a superb example of namban lacquerware, made for export to Europe in the early seventeenth century. This game board would be used to play what is known in Japan as “European sugoroku,” which is to say backgammon. Both that game and Japanese ban sugoroku (board sugoroku), which have similar origins, date back to the period in the eighth through the tenth centuries, when treasures were being stored in the Shosoin in Nara. Written accounts tell us that people from every level of society played them enthusiastically. Despite sugoroku being prohibited again and again, it continued to be a popular form of recreation up through the early modern period.

In Edo-period pictures of amusements, we almost always see men and women playing board sugoroku as well as depictions of the boards themselves. Moreover, the sugoroku board, the Go board, and the shogi ( Japanese chess) board became the set of three boards that were among the furnishings in a bride’s trousseau. Later, another game, the much simpler e-sugoroku (picture sugoroku), rapidly grew in popularity from the closing years of the Edo period on to the modern period. The colorful printed sheets for playing the game became familiar both as New Year’s games and children’s toys. All these sugoroku games, in which the outcome depends in part on the roll of the dice, are richly involved in the history of negotiations between East and West and in cultural history, especially the history of play.

Momoyama period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【To be shown over an entire period】

Momoyama period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【To be shown over an entire period】

Attributed to Kano Sanraku

Right screen of pair of six-panel folding screens (detail)

Momoyama period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art

【To be shown between Jun.26 and Jul.22】

7. Changes in Karuta (Card) Games:

From Unsun Karuta to Hanafuda

Karuta (card) games were introduced to Japan from Portugal during the Namban cultural exchanges (exchanges with the “southern barbarians,” mainly the Portuguese, in the sixteenth century). Starting with the designs of the Portuguese cards and the rules of those card games, games such as Tensho Karuta and Unsun Karuta were born and become, with their exotic air, quite popular. The series of “house of pleasure” paintings, for example, depict poker-faced men and women absorbed in applying their strategies as they play karuta. The Hyakunin-isshu (One poet, one poem) karuta, with their connection to waka poetry, emerged later and other games that enabled people to acquire some of the knowledge they would need as adults through playing karuta games.

The history of karuta is thus also a history of learning while having fun. The cards later evolved into hanafuda, with flowers rather than numbers, which were also sometimes used in gambling. Another variant was the i-ro-ha karuta, which was popular in the closing years of the Edo period and in the Meiji period; while the name of the game was the same, its content differed in the Kyoto and Edo areas. Each card thus carries information that is endlessly fascinating in terms of cultural history.

Edo period, 17th century

Tekisui Museum of Art

【To be shown over an entire period】

8. The Genealogy of “Merrymaking” in Art (3) :

Dance and Fashion

Scanning depictions of amusements at the start of the early modern period (Momoyama to early Edo), we can identify several features common to all of them. One is the presence of the shamisen. Whether indoors or out, the shamisen is the dominant source of the tunes and rhythms flowing through amusement areas at the start of the early modern period.

A second shared feature was a growing interest in dance and fashionable clothing. The hairstyles and clothing worn by the men and women in pictures of merrymaking suggest their inclination to remain constantly at the leading edge of fashion trends. The dancers’ appearance as they take part in round dancing or dance with a fan in one hand summons up the mood of people at play, the true stars of depictions of merrymaking, throughout history. Exchanges of letters between men and women might be in the hands of the young servants called “letter bearers.” But the mingled gazes and the expressions of those people, their hearts moved by the letters’ contents, suggest that the letter may be another form of amusement.

These amusements are the common elements that can be discovered in pictures of merrymaking, though the relative importance of each type of play varies. Over time, an obsession with fashion would develop into works focused on the kimono itself, such as the Kimono on Hanging Racks folding screens, while an interest in the dancing bodies developed into Dancers and other works depicting dancing. Moreover, during the Kanbun era (1661-1673), single female figure portraits, the Kanbun Beauty, became fashionable, laying the ground for the birth and the popularity of ukiyo-e.

Right screen of pair of six-panel folding screens (detail)

Edo period, 17th century

The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

【To be shown between Jul.24 and Aug.18】

Two-panel folding screen

Edo period, 17th century

The Tokugawa Art Museum

© The Tokugawa Art Museum Image Archives / DNPartcom

【To be shown between Jun.26 and Jul.15】

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2024 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

2024 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31