- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

Kawanabe Kyosai: Nothing Escaped His Brush

February 6 to March 31, 2019

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition

*Download the list of changes in works on display

The list of changes in worksPDF

Section 1

Kyosai is Here!

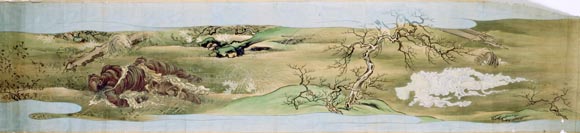

Kyosai, famed for his technique, has left us superb works in a host of genres, including Buddhist subjects, bird-and-flower paintings, and images of beautiful women. In 1881, his Winter Crow on a Withered Branch was awarded the highest prize given at the Second Domestic Industrial Exposition, and Kyosai’s reputation as an artist soared. This scroll expresses the essence of ink painting. In contrast, his polychrome painting Birds and Flowers, which was displayed in the same exhibition, shows a skilful and precise rendering of vivid colors. Comparing these two works reveals the breadth of Kyosai’s art. He also created many sekiga. These impromptu paintings produced at banquets and other events display the distinguishing power of his brushwork. In many other works, however, we see him developing his concept slowly with an unsparing dedication. These paintings demonstrates Kyosai’s attention to details and his outstanding artistic skills.

This section features Kyosai’s masterpieces which best exemplify his artistic achievement.

Kawanabe Kyosai, 1881, Eitaro Sohonpo Co., Ltd.

【To be shown between Feb. 6 and Mar. 4】

Kawanabe Kyosai, 1881, Tokyo National Museum

Image: TNM Image Archives

【To be shown between Feb. 6 and Feb. 18】

Section 2

As a Kano-school Artist

Kyosai was ten when he began studying with Maemura Towa of the Surugadai Kano school. Towa loved his talent and called Kyosai “the demon of painting.” The following year, when Towa fell ill, Kyosai moved to the studio of Towa’s own teacher, Tohaku Norinobu, the seventh-generation head of the Surugadai Kano school. There he acquired the fundamentals of the Kano-school painting. Kyosai rapidly distinguished himself. In 1848, at the age of nineteen, having completed his training exceptionally quickly, he was given the art name Toiku Noriyuki. His connection with the Kano school did not, however, end there. When Toshun, the ninth-generation head of the Surugadai Kano school was on his deathbed in 1884, he asked Kyosai to respectfully preserve the painting techniques of the school. Subsequently, he restarted his training under Eitoku Tachinobu (1814-91), of the main branch of the Nakabashi Kano school. His connection with the Kano school continued until the end of his life. Kyosai painted in a variety of styles, but his work was rooted in the powerful brushstrokes and well-balanced compositions he had mastered as a Kano-school painter.

This section presents Kyosai’s works from his early days as a Kano-school student as well as paintings that demonstrate his use of Kano school techniques and themes throughout his career.

Kawanabe Kyosai, 1848, Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum

【To be shown between Feb. 6 and Mar. 4】

Kawanabe Kyosai, Shogyoin Temple, Tokyo

【To be shown over an entire period】

Section 3

Learning from the Classics

Many of Kyosai’s works demonstrate his study of classical paintings with an added individuality. He thus breathed new life into long-established subjects. His Kyosai Gadan (Kyosai’s treatise on painting), which he illustrated, contains many copies of his predecessors’ works. It includes works of distinguished Song and Yuan dynasty painters, Sesshu and other medieval Japanese masters, plus many generations of Kano-school artists such as Motonobu and Tan’yu. The book also features Tosa and Maruyama school painters as well as Ogata Korin and Tani Buncho. Furthermore, there are ukiyo-e artists such as Suzuki Harunobu, Kitagawa Utamaro and Katsushika Hokusai. Thus the book reveals how widely Kyosai studied masterpieces from the past. Several of his copies of classical paintings, in handscroll and album format, are also extent. From them we know that he passionately copied designs with the original before his eyes.

The Kano-school training process begins with copying the compositions of the masters, both Japanese and Chinese artists. Only after the student made serious progress, would he be allowed to assist his teacher in actually painting a work. Kyosai’s own study of the classics continued until the end of his life and the fundamentals of the Kano school were at the core of his creative activity.

In this section, we compare Kyosai’s sources with his own paintings in order to examine how he addressed the classics and refined what he learned from them in his own work.

Kawanabe Kyosai, Prior to 1871, Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum

【To be shown over an entire period】

Kawanabe Kyosai, Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum

【To be shown between Mar. 6 and Mar. 31】

Section 4

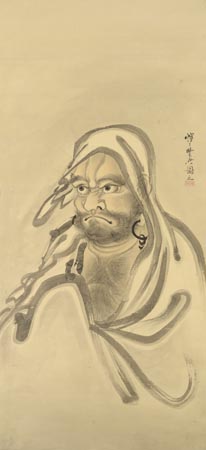

Playful Pictures

Kyosai’s humorous works such as pictures of party scenes and various caricatures have many passionate proponents. Indeed, the image of Kyosai as the satirical caricaturist has penetrated so deeply that sometimes too much is read into depictions that are not actually satirical in intent. In fact, weren’t sekiga, the impromptu performance paintings that he produced at drinking parties and other events meant to be playful art to the artist himself?

Kyosai’s comic pictures have been discussed, thus far, in terms of his relationship with his first teacher, Utagawa Kuniyoshi. The fact that a great many humorous images were produced by members of Kano Tan’yu’s circle, however, has only recently come to light. We also know that Kyosai owned such paintings by Tan’yu, and it is likely that they had a major influence on Kyosai’s work in this area.

This section looks at Kano-school playful imagery and Kyosai’s paintings of people having fun, caricatures, and sekiga that still retain a deeply rooted popularity.

Kawanabe Kyosai, 1886

Israel Goldman Collection, London (formerly in the collection of Josiah Conder)

Photo: Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University

【To be shown over an entire period】

Section 5

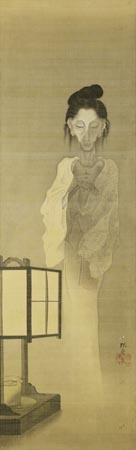

The Sacred and the Profane, the Beautiful and the Ugly

The sacred and the profane, the living and the dead, the beautiful and the frightful: Kyosai’s worldview, which places these contrasting subjects in juxtaposition, is one of the reasons his work is so compelling. What at first glance seems to be a picture of a beautiful woman has a complex story woven into its background. A frightening painting of a ghost conveys a sense of a beauty that has passed in days gone by. Kyosai’s mingling of contradictory values is made possible by his extraordinary abilities as a painter.

In this section, we explore Kyosai’s paintings of the human figure, in which he expresses the psychological subtleties of his subjects.

Kawanabe Kyosai, 1879-89, Hayashibara Museum of Art

【To be shown between Mar. 6 and Mar. 31】

Kawanabe Kyosai, ca.1868-70

Israel Goldman Collection, London

Photo: Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University

【To be shown over an entire period】

Section 6

Gemlike Masterpieces

What are Kyosai’s masterpieces? His large, powerful paintings are impressive, but he also created many fascinating works in small formats. In particular, his albums, each created for a particular client so that the person who commissioned it could keep it at their side and enjoy it whenever they wished, are particularly exquisite examples. Their leaves, each painted in precise colors, down to the finest detail, never cease to delight.

Here we introduce the world of Kyosai’s albums, each a world in a jewel box.

Kawanabe Kyosai, Prior to 1871, Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum

【To be shown over an entire period】

Section 7

Kyosai’s Networks

Kyosai’s genius attracted numerous admirers. Most significant amongst them was the British architect Josiah Conder (1852-1930). Conder came to Japan as a foreign government advisor and became Kyosai’s student. They developed especially strong ties of mutual respect and trust. In fact, Conder was present at Kyosai’s death. After Kyosai died, Conder published Paintings and Studies by Kawanabe Kyosai, a comprehensive catalogue of Kyosai’s work which was a major factor leading to Kyosai’s growing fame overseas.

Many temples, shrines, and restaurants throughout Japan own paintings that Kyosai donated directly to them. It is also known that many people clamoured to acquire his works. His Calligraphy and Painting Party illustrates the artist’s popularity. It shows him deluged by too many commissions which he was unable to fulfill. The Kyosai E-Nikki (Kyosai’s Illustrated Diary), a record of his daily life, provides a glimpse of his circle of friends and acquaintances, including a number of cultural figures who called on him and with whom he built close ties.

This final section focuses on the works that were once owned by those who knew Kyosai or in places with personal connections to the artist. They demonstrate the breadth of the cultural network formed around him.

Kawanabe Kyosai, 1885

Israel Goldman Collection, London (formerly in the collection of Josiah Conder)

Photo: Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University

【To be shown over an entire period】

Kawanabe Kyosai, 1874, Yushima Tenmangu Shrine, Tokyo

【To be shown over an entire period】

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2024 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

2024 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31