- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

Celebrating a Decade in Roppongi

Kano Motonobu: All Under Heaven Bowed to His Brush

September 16 to November 5, 2017

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition

*Download the list of changes in works on display

The list of changes in worksPDF

Section 1

Becoming the Artists to Whom All Bowed Down:

The World of Wall and Sliding Door Paintings

The Kano school maintained its position at the top of the art world for about four centuries, from the Muromachi period until the closing years of the Tokugawa shogunate. Founded by Kano Masanobu (1434-1530), it had only the status of a secondary school during his lifetime. It was his son and second-generation head of the Kano school, Motonobu (1477?-1559), that made it supreme. A history of the school, Honcho Gaden (Compendium of artists’ biographies and the history of painting in Japan), was published in 1691 by Kano Eino (1631-97), the third-generation of the Kyoto branch of the Kano school. According to that book, believed to be the first art history book published in Japan, the Kano school became "the artists to whom all bowed down" in Motonobu’s day. He was, thus, the recognized founder within the Kano school itself.

What speaks most directly of the school’s rapid growth are the wall and sliding door paintings that Motonobu and his students created. These paintings, commissioned by temples to decorate elements of the buildings themselves, were large-scale projects closely connected to the structures of the temple buildings and tested the capabilities of Motonobu as a master artist leading his team. Many of those wall and sliding door paintings have been remounted as hanging scrolls, but their precise composition and depiction still demonstrate to us how Motonobu’s brilliant spatial presentation met the expectations of those commissioning his works. In addition, the group of works that Motonobu is thought to have painted himself demonstrate that, beyond his resourcefulness as a team leader, his superb painting skills were without peer. In this section, we introduce wall and sliding door paintings that are now historically significant works, monuments to the achievements of Motonobu and his workshop.

Flowers and Birds of the Four Seasons (Important Cultural Property)

Kano Motonobu, Four of eight hanging scrolls

Muromachi period, 16th century, Daisen-in Temple, Kyoto

【To be shown between Sep.16 - Oct.2 and Oct.18 - Nov.5】

Patriarchs of Zen Buddhism (Important Cultural Property)

Kano Motonobu, Six hanging scrolls

Muromachi period, 16th century, Tokyo National Museum

Image:TNM Image Archives

【To be shown between Sep.16 and Oct.23】

Section 2

Copying the Masters: Famous Artists, Objects of Adoration

Admiration for the work of famous Chinese artists remained strong throughout the Muromachi period. The collection of Chinese paintings assembled by the Ashikaga shogun clan set the standard for production of Chinese-style paintings by Japanese artists. The Chinese artists in the Ashikaga collection were mainly from the Southern Song period and included Ma Yuan, Xia Gui, Muxi, and Yujian. Japanese artists were expected to emulate their compositions and methods of depiction. The works created in those hitsuyo, “brush styles,” were identified by the names of the famous artists being imitated: “In the manner of Ma Yuan,” “Xia Gui style,” and so on. While taking the same Chinese artists as their models, Japanese painters had their individual differences, with considerable variations in their styles. It was Motonobu who devised three painting styles, shin, gyo, and so, or, respectively, formal, semi-formal, and informal, instead of the diverse “brush styles,” and produced a manual for training in the Motonobu style. He thus created the framework for creating groups of paintings that would maintain a set level of quality. Motonobu took the rather angular style of Ma Yuan and Xia Gui as his reference for the shin, formal, style, the soft ink-wash style of Muxi for the gyo, semi-formal, style, and the broken ink style of Yujian for the so, or informal style. He also extracted separate motifs related, for example, to the human figure, birds and flowers, and trees, and incorporated them into his work.

This section presents famous Chinese paintings that Japanese artists found inspirational, including Southern Song paintings and Ming dynasty works by Lu Ji and other artists who carried on that tradition.

Section 3

Establishing Defined Paintings Styles: Shin, Gyo, and So

Motonobu’s establishment of defined painting styles significantly changed how the Kano school operated. The three styles, or gatai, consist of the shin, the formal style with precise composition and brushwork, the informal or cursive so style, with its freer brushwork, and the semi-formal gyo style in between. Those names are modeled on terms for three styles of calligraphy: kaisho, gyosho, and sosho, or regular, running (semi-cursive), and cursive. Unlike the earlier hitsuyo styles, these painting styles were reorganized as the Motonobu style and defined a consistent style. Motonobu’s family members and students then mastered those styles, so that multiple painters were capable of working in the Motonobu style. The consistency of style achieved by his workshop made group projects possible and furthered the development of the Kano school as a body of professional artists.

The gatai or painting styles chosen were deeply related to the type or formality of the interior space for which paintings were being created. They also played a critical role in “performance of space.” For example, wall and sliding door paintings for temples, castles, and other structures would be produced in the formal shintai (shin style) for public reception rooms, while the less formal gyotai (gyo style) and sotai (so style) were used extensively in the private living quarters of Kano clients.

This section displays superb works based on the shin, gyo, and so styles Motonobu created as well as major works by Kano Masanobu, Motonobu’s father.

Eight Scenic Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers (Important Cultural Property)

Kano Motonobu, Four hanging scrolls

Muromachi period, 16th century, Tokai-an Temple, Kyoto

【To be shown between Oct.4 and Oct.16】

Section 4

Combining Japanese and Chinese Painting Styles

Motonobu, beyond his major achievement in establishing his gatai or styles in Chinese painting, also made notable strides in the field of Yamato-e or Japanese-style painting. In his father’s day, the Kano school was understood as consisting of artists specializing in Chinese-style painting. In Motonobu’s generation, the Kano school advanced into the Yamato-e terrain, then dominated by the Tosa school. Effective use of painting themes and techniques that synthesized Japanese and Chinese styles became the Kano school hallmark. Thus, the Honcho gaden (Compendium of artists’ biographies and the history of painting in Japan) by a Kano school member, states, “It was the Kano family who combined Chinese and Japanese styles.”

Picture scrolls and fan paintings that combined the clear, strong compositions and line drawing of artists in the Chinese tradition with the use of gold pigment and rich colors associated with Yamato-e are the best examples of Motonobu’s Japanese-Chinese synthesis. Fan paintings, for which demand, as gift exchange items, was strong, became a major source of income for the Motonobu workshop. The richly expressive depictions of people in those fan paintings and in Mandala of Pilgrimage to Mt. Fuji that Motonobu painted tell us that he did far more than appropriate the Yamato-e genre style: he refined and developed it further.

This section focuses on Motonobu’s daring new synthesis of Japanese and Chinese styles, particularly in picture scrolls and fan paintings.

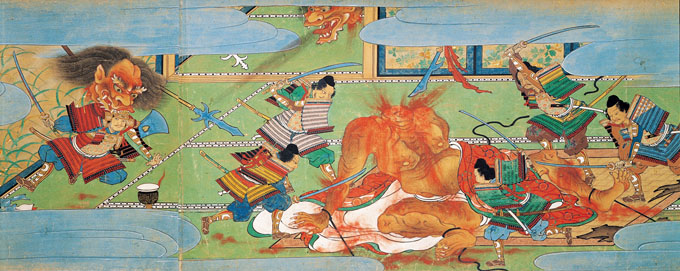

Conquest of Goblin Shuten-doji (Important Cultural Property)

Painting by Kano Motonobu, calligraphy by Konoe Hisamichi, Johoji Kojo, and Shoren’in Sonchin

Volume 3 (detail), One of three handscrolls

Muromachi period, dated 1522, Suntory Museum of Art

【To be shown over an entire period】

Miscellaneous Fan Paintings of Monthly Events in Kyoto

(Tangible Cultural Property Designated by Kyoto City)

With Motonobu seal, Six-panel screen

Muromachi period, 16th century, Koen-ji Temple, Kyoto

【To be shown between Oct.11 and Nov.5】

Section 5

Depicting Faith

From the Heian period on, Buddhist religious paintings had been a field dominated by ebusshi, artists, usually associated with temples, who specialized in this field. Temple in Nara and Kyoto were the main centers for the production of such paintings. Masanobu and Motonobu, however, added Buddhist paintings to their repertoire. The vivid colors and worldly expressions found in their work were significantly different from traditional Buddhist paintings, and their distinctive styles breathed new energy into the Buddhist genre.

The White-robed Bodhisattva of Compassion is regarded as Motonobu’s ultimate masterpiece in Buddhist painting. Its delicate depiction of the Bodhisattva’s features, the agile, sharp lines defining the robes, the descriptive powers visible in the rocks and waves, and the balanced composition all make it a magnum opus.

This section introduces works on religious subjects, including both Buddhist and Shinto paintings, by both Masanobu and Motonobu, and shows how they broadened their spheres of activity by moving into new terrains.

White-robed Bodhisattva of Compassion

Kano Motonobu, Hanging scroll

Muromachi period, 16th century, Seikado Bunko Art Museum

©Seikado Bunko Art Museum Image Archives/DNPartcom

【To be shown between Sep.16 and Oct.9】

Section 6

Broader Patronage

Motonobu’s work, in which he freely and effectively applied his varied subject matter, techniques, and formats to meet the preferences of those commissioning it, attracted a broad range of admirers. His father, Masanobu, had had the Muromachi shogunate and the Gozan or five major Zen temples as his main patrons. Motonobu also received commissions from the imperial family, aristocrats, and wealthy townsmen, a class that had become more powerful. He had close ties to his patrons, as attested by his portraits of those who commissioned his work and by the votive pictures, to be dedicated at shrines by those praying there, that he created. Motonobu himself worked actively to acquire customers. An example of those efforts can be seen in his Letter to Master of Gyokuun-ken Household, in which he asks the priest’s assistance in making contact with Kizawa Nagamasa, a powerful general in the Kyoto area.

Expanding the school’s base of support became a driving force in the multifaceted creative activities of Motonobu and his students. This final section of the exhibition focuses on the breadth of Motonobu’s network and the Kano school’s establishment of its leading position in the art world.

Portrait of Warrior Hosokawa Sumimoto (Important Cultural Property)

Kano Motonobu, with inscription by Keijo Shurin, Hanging scroll

Muromachi period, inscription dated 1507, Eisei-Bunko Museum

【To be shown between Sep.16 and Oct.9】

Kano Motonobu, Two panels

Muromachi period, 16th century, Kamo Shrine, Hyogo

Picture provided by Tokyo National Museum, Image:TNM Image Archives

【To be shown between Sep.16 and Oct.23】

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2026 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31