- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

Treasures of the Fujita Museum:

The Japanese Conception of Beauty

August 5 to September 27 2015

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition.

Section 1

Denzaburo and the Anti-Buddhist Movement

Fujita Denzaburo was born in 1841 in Hagi, Choshu (now Yamaguchi Prefecture) to a family of saké brewers, during the Bakumatsu period, the closing years of the Tokugawa shogunate. Hagi is famous as the home of Bakumatsu activists and revolutionaries such as Yoshida Shoin and Takasugi Shinsaku. Denzaburo was in his late twenties and living in Hagi when the revolutionaries’ efforts resulted in the Meiji Restoration.

After the Restoration, many of the young people who had been active in the revolution became government officials. Denzaburo, however, decided to contribute to Japan’s modernization by working in the private sector. Moving to Osaka, he became a military contractor, providing supplies and labor to the defense contractors. He then became involved in a wide range of enterprises: building railroads, tunnels, and bridges, land reclamation, canal building, and operating a coal mine. In the process, he became one of the Kansai region’s leading entrepreneurs.

The revolution known as the Meiji Restoration led to Japan’s rapid modernization, a process from which Denzaburo benefitted. The new government’s policy of Europeanization and modernization, however, also led to the disintegration of Japan’s traditional culture. Denzaburo was particularly concerned that the new regime’s anti-Buddhist movement would lead either to the destruction of Buddhist works of art or their becoming dispersed overseas. To prevent their loss, he invested his personal funds in efforts to protect those cultural assets.

This section introduces superb examples of religious art preserved for later generations by the Fujita family.

Important Cultural Property

Standing Jizo Bosatsu (Sk. Ksitigarbha)

By Kaikei

Kamakura period, 13th century

Fujita museum

Photo: Miyoshi Kazuyoshi

National Treasure

Divinely Inspired Reception of the Two Great Sutras of Esoteric Buddhism

By Fujiwara no Munehiro

One of two framed paintings

Heian period, dated 1136

Fujita museum

Section 2

A National Culture

Denzaburo’s art collection was by no means merely a hobby. He was committed to preserving Japan’s traditional works of art. Believing that a nation’s foundation was its culture, Denzaburo, after much thought, decided to build a systematic collection of works of art that Japanese had appreciated for hundreds of years. The rich array of paintings, calligraphic works, and superb examples of lacquerware and textiles collected by Denzaburo and his sons testifies to the power of the sensibilities and ideas that drove them.

In this section, we introduce masterpieces of Japanese calligraphy and painting from Japan’s Middle Ages. As a distinctively Japanese national culture emerged and developed during the Heian period, kana, syllabic Japanese scripts, were created. One of the characteristics of kana is a touch of softness in their forms. The rise of kana gave the Japanese freedom to express themselves through writing in their own language and contributed significantly to the development of waka, Japanese poetry, as well as prose narratives and other literary forms.

The most important art form for depicting such narratives was the picture scroll. Exploring the history of Japanese art, we realize that hanging scrolls, folding screens, and many other formats for paintings were imported to Japan from China. The picture scroll was no exception. While its roots do lie in Chinese picture scrolls, this medium developed further in Japan, evolving into a distinctive type of painting depicting, for example, prose narratives.

National Treasure

Sutra Box (Kyobako), with illustrations of Buddhist virtue in makie lacquer

Heian period, 11th century

Fujita museum

Photo: Miyoshi Kazuyoshi

National Treasure

Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Ekotoba (Illustrated Diary of Murasaki Shikibu)

One scroll (detail)

Kamakura period, 13th century

Fujita museum

National Treasure

Genjo Sanzo'e( Illustrated Life of the Tripitaka Master Xuanzang)

1st of twelve scrolls (detail)

Kamakura period, 14th century

Fujita museum

Section 3

The Hanging Scrolls Tea Master Denzaburo Loved

In the course of the enormous social changes that followed the Meiji Restoration, interest in what had been traditional cultural activities swiftly declined. Even the tea ceremony lost many adherents. In time, however, rising members of the political and business establishment developed an intense interest in the world of tea. They generated a vogue for a new culture of elegant pursuits, of which the tea ceremony was a part, and the preservation of Japanese art. Denzaburo himself studied the Mushakoji Senke and Omote Senke schools of tea and, as a modern man of refinement with a taste for the tea ceremony, interacted socially with Inoue Kaoru (Segai), a senior statesman who was also from Hagi, and Masuda Takashi (Donnoh), the founder of Mitsui & Co., Ltd., one of Japan’s largest general trading companies.

The history of the tea ceremony begins with transmission, followed by evolution. Through Zen Buddhism, the custom of appreciating tea, along with ink paintings and calligraphy, was introduced from China. What we now know as the tea ceremony then underwent significant development in Japan. When the tea ceremony as we now know it emerged in the mid Muromachi period (1392-1573), kara-e, paintings from Song and Yuan dynasty China, were regarded as the ideal hanging scrolls to decorate the tokonoma alcove in a tea house. One of the most important procedures in the tea ceremony is admiring a hanging scroll in the tokonoma of the tea house when you enter it. Over time, however, calligraphy by Zen priests in Japan took their place.

This section introduces masterpieces of hanging scrolls that Denzaburo and his friends enjoyed displaying in the tokonoma, including calligraphy and Song and Yuan dynasty paintings together with Japanese ink paintings that emulated them.

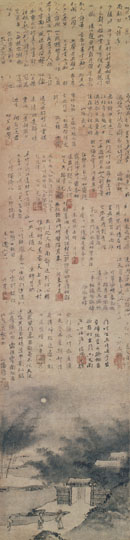

National Treasure

Saimon Shingetsu (Newly Risen Moon above the Brushwood Gate)

One hanging scroll

Muromachi period, dated 1405

Fujita museum

Section 4

A Shared Passion for the World of Tea

The esteem and high social position resulting from Denzaburo’s business success led to his involvement in founding other companies as well as his own. These included the predecessors of what are now the Nankai Electric Railway Co., Ltd., Toyobo Co., Ltd., and the Kansai Electric Power Co., Inc. His contributions to creating social infrastructure included founding the Osaka Chamber of Commerce (now the Osaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry), helping revive the Osaka Mainichi Newspaper (now part of The Mainichi Newspapers), and contributing large sums for educational purposes.

Denzaburo’s warm, gentle personality won him not only popularity but also access to famous tea wares. Denzaburo’s journal of tea gatherings and other documents were, unfortunately, lost during World War II. The story is told, however, that ten days before his death, he acquired an extraordinary piece he had long ardently desired, the Incense Container (Kogo), Cochin-ware with turtle-shaped lid (cat. no. 92). His sons carried on their father’s passion. His elder son, Heitaro, added the Tea Bowl (Chawan), Tenmoku glaze with glistening spots (Jp. yohen) (cat. no. 72), one of the most famous tea bowls in the world, to the collection, while his younger son Tokujiro acquired the Tea Bowl (Chawan), Goshomaru type, black-brushed (kurohake) motif, named Sekiyo (Evening Sun) (cat. no. 74).

This section introduces the famous tea wares that Denzaburo and his sons collected so passionately.

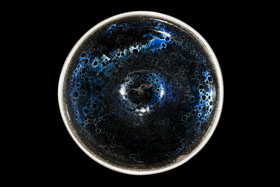

National Treasure

Tea Bowl (Chawan),

Tenmoku glaze with glistening spots (Jp. yohen)

China, Southern Song dynasty, 12th-13th century

Fujita museum

Photo: Miyoshi Kazuyoshi

Incense Container (Kogo),

Cochin-ware with turtle-shaped lid

China, Ming-Qing dynasty, 17th century

Fujita museum

Photo: Miyoshi Kazuyoshi

Section 5

A Man of Unparalleled Taste

The Fujita family owned a large estate in Amijima-cho, Miyakojima Ward, Osaka, a location that had been the setting for Chikamatsu Monzaemon’s play The Love Suicides at Amijima. Denzaburo personally designed the mansion and garden built on that site. While the residence was almost entirely destroyed in the 1945 bombing of Osaka, one storehouse has survived and now serves as the Fujita Museum gallery.

Denzaburo is known in the business world as the man with the finest taste in the tea ceremony, architecture, garden design, and Noh. He enjoyed both studying Noh and watching performances with his family and even had a Noh theater in his residence. Thus, the Fujita family collection also includes Noh costumes and masks, some which they may have actually worn while dancing in Noh performances.

Denzaburo and his sons were interested not only in antique works of art but also the work of contemporary artists. They collected, for example, the work of artists such as the modern Japanese-style (Nihonga) artist Takeuchi Seiho (1864-1942).

This section introduces the breadth of the Fujita family collection.

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2024 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

2024 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31