- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

Celebrating Two Contemporary Geniuses:

Jakuchu and Buson

March 18 to May 10 2015

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition.

Chapter 1

Kyoto’s Eighteenth-Century Renaissance

The year Shotoku 6 (1716) was a significant one in the history of Japanese premodern art. It was the year that Ito Jakuchu was born the eldest son of the owner of a grocery wholesale businesses in Kyoto called Masuya and Yosa Buson was born in the village of Kema in Settsu province (now part of Osaka and of Hyogo prefectures). It was also the year when Ogata Korin, leader of the glories of Genroku culture, died in Kyoto. In Edo, Tokugawa Yoshimune that year became the eighth shogun of the Tokugawa bakufu. He eased restrictions on the import of Western books and allowed trade in rare things from overseas. The Obaku sect of Zen Buddhism was introduced to Japan and various books on painting and other publications from Qing dynasty(China) found their way to its shores,stimulating new currents in the painting circles in the Edo period.

This exhibition shows the depictions of human figures, landscapes, flowers and birds, and the like of the two artists as they unfolded with their respective lives. This first chapter provides a glimpse of the lively and vibrant atmosphere of eighteenth-century Kyoto, where the two artists lived.

Hanshan and Shide

by Ito Jakuchu

Pair of hanging scrolls

18th century

Private Collection

Chapter 2

Beginnings and Training

It is not clear when either Jakuchu or Buson began painting. Jakuchu first studied the techniques of the Kano school and later pursued new techniques by studying and copying Chinese and Korean paintings owned by big Kyoto temples like Shokokuji. After that he began to emphasize the realistic representation of living things; for example, he would release roosters and hens in his garden and sketch their movements.

Buson, on the other hand, moved to Edo at the age of around 20 and studied haikai poetry, but after his haikai teacher died, he traveled for ten years, first in the northern Kanto region and then in the Tohoku region. His paintings during that time were created in an idiosyncratic style, distinct from the conventional techniques of the Kano and other schools. He then settled in Kyoto; from the spring of 1754 (Horeiki 4) to autumn 1757 (Horeki 7), he resided Tango province (north of the city), devoting his time to painting.

Chapter 3

Establishment of Painting Styles

Jakuchu, who had turned 40 years old and retired from the family business after handing the management of the Masuya store over to his younger brother, now devoted himself to painting. He eventually set to work on the production of one of his major works, the Doshoku sai-e (Colorful Realm of Living Beings; now in the collection of Kunaicho Sannomaru Shozokan, or the Museum of the Imperial Collection). He also produced large-scale suibokuga (ink paintings) such as the screen and wall paintings at Rokuonji temple in Kyoto. By actively painting various subjects sometimes in richly colored pigments and other times in monochrome ink, he established a distinctive style centering around flower-and-bird paintings.

Buson moved to Kyoto in his early forties. There he painted a wide variety of subjects including flowers and birds under the influence of the works of Chinese painter Shen Quan (Shen Nanpin; 1682-ca. 1760), who was very popular in Japan in those days, as well as landscapes after the style of Chinese literati painting. In particular, the byobu folding screens he made for the Byobu Ko, an association organized and financed by his haikai poetry associates for purchase of fine byobu screens, were wonderful works created within a short period of time using an abundance of expensive pigments. In his early 50s he also visited Sanuki province (now Kagawa prefecture).

In this way Jakuchu and Buson in their forties and fifties produced many splendid paintings of great vigor and mature technique.

Chapter 4

New Challenges

Most notable among Jakuchu’s suibokuga ink paintings are a group of works done with a distinctive brush technique known as sujime-gaki. The technique takes advantage of the soft and absorbent texture of the gasenshi paper, which makes it possible to execute strokes in sumi ink even very close to each other without the ink merging, leaving the space between them looking like a white line, or sujime. Jakuchu’s dragons and chrysanthemums in skillful sujime are captivating.

Buson, meanwhile, developed and led a new genre called haiga consisting of a painting and a hokku (haikai) poem that resonate with each other. His seemingly casual style of haiga painting reflects the insights and subtlety he had developed through his haikai poetry.

The works shown here suggest that Jakuchu and Buson, neither of them satisfied with conventional painting, kept on taking up the challenges of new techniques.

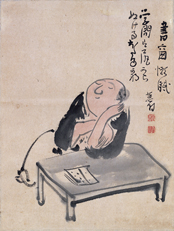

Man Dozing at His Desk

by Yosa Buson

18th century

Private Collection

The Narrow Road to the Deep North Handscroll(detail)

by Yosa Buson

An’ei 7 (1778)

Umi-Mori Art Museum

Chapter 5

Influences from Chinese and Korean Painting

As is clear from his own works, Jakuchu studied Chinese painting techniques, especially of the Yuan and Ming periods, in works owned by Shokokuji and other large temples. Buson, too, appears to have studied from Chinese paintings of the Ming and Qing periods that were in circulation in those days.

Chinese painter Shen Quan (Shen Nanpin), who had arrived in Nagasaki in 1731, won great popularity for his realistic depictions of flowers and birds. Obaku-sect priest Kakutei, one of Shen Quan’s second generation disciples in Japan, passed on his style of painting to Kyoto and other parts of the Kinki region. Shen Quan greatly influenced the art world of the region, a world of which Jakuchu and Buson were a very active part. Among their works done during the Horeki era (1751-1763) are animal paintings obviously done in the Shen Quan style.

This chapter introduces works of Chinese and Korean painting, as well as the world of art of their era, that seem to have been related in some way or other with the activities of Jakuchu and Buson.

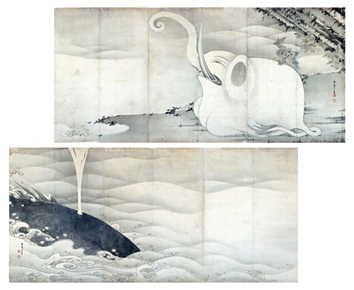

White Elephant and Other Animals

by Ito Jakuchu

18th century

Private Collection

Chapter 6

Proximity and Mutual Acquaintance

In his later years Buson moved to live close to the Shijo Karasuma area of Kyoto where Jakuchu resided. Although more than 500 letters by Buson have been preserved, none of them make any mention of Jakuchu. No work or document from those days has been discovered so far that would indicate they knew each other. Among their works, however, there are some that bear legends written by the same Zen priests and the same noted scholars; it is known that they had common friends and acquaintances, such as Ikeno Taiga, Maruyama Okyo, Ueda Akinari, Minagawa Kien, and Kimura Kenkado.

This chapter introduces works by Jakuchu and Buson jointly created with or with legends by people of their acquaintance, including Jakuchu’s younger brother Hakusai and Buson’s disciples.

Monkeys and Peach Tree

Painted by Ito Jakuchu, Inscription by Hakujun Shoko

18ht century

Private Collection

Chapter 7

Later Years

Late in his life Jakuchu used the pseudonym of Beito-o, which literally means an “old man” (o) who produces a piece of painting for one-“to” (18 liters) of “bei” (rice). Buson, too, began using the pseudonym Yahan-o (lit., “midnight old man”) from 1770 when he succeeded his haikai teacher as Yahantei II. Despite calling themselves “old men,” they both stayed very active and were very productive.

This chapter presents works from their later years, mainly those works signed by Jakuchu as “Beito-o” and by Buson as “Yahan-o” and later “Sha’in.”

Elephant and Whale Screens

by Ito Jakuchu

Pair of six-panel screens

Kansei 9 (1797)

Miho Museum

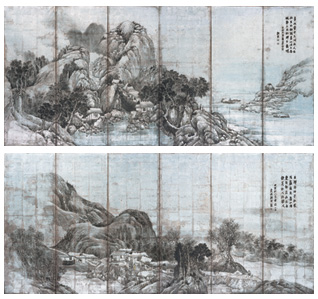

Landscape

Pair of six-fold screens

by Yosa Buson

Tenmei 2 (1782)

Miho Museum

Plank Road to Shu

by Yosa Buson

Hanging scroll

An’ei 7 (1778)

LING SHENG PTE. LTD(Singapore)

Important Cultural Property

Kite and Crows

by Yosa Buson

Pair of hanging scrolls

18th century

Kitamura Museum

Important Cultural Property

Mt. Fuji and Pines by Yosa Buson

18th century

Kimura Teizo Collection, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2024 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

2024 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2024 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2024 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31