Suntory Hall Summer Festival 2023

Theme Composer OLGA NEUWIRTH

Echoing between a rock and a hard place

On the work of Austrian composer Olga Neuwirth

The Theme Composer of Suntory Hall Summer Festival 2023 (August 23-28) is the highly acclaimed Austrian composer, Olga Neuwirth. A selection of her major works, including the world premiere of the new orchestral commission Orlando’s World, derived from her recent opera Orlando, will be featured in the two portrait concerts. Vienna-based Music Critic Walter Weidringer discusses Neuwirth’s unique musical cosmos and artistic trajectory from her youth in provincial Austria to international success.

“I would prefer not to”, says the title figure one day in Hermann Melville’s short story Bartleby the Scrivener (1853). Gently but resolutely expressed, Bartleby’s resistance begins in the same Wall Street law office where previously he dutifully copied out contracts. It keeps escalating, evolving from a refusal to function to a kind of rejection of life itself. Olga Neuwirth is fascinated by the person and the work of the Moby Dick creator Melville. She has now produced numerous works inspired by him – an extensive enterprise taking many forms, including a multimedia meta-composition: the volume O Melville combines photo series, essays and even a film on DVD.

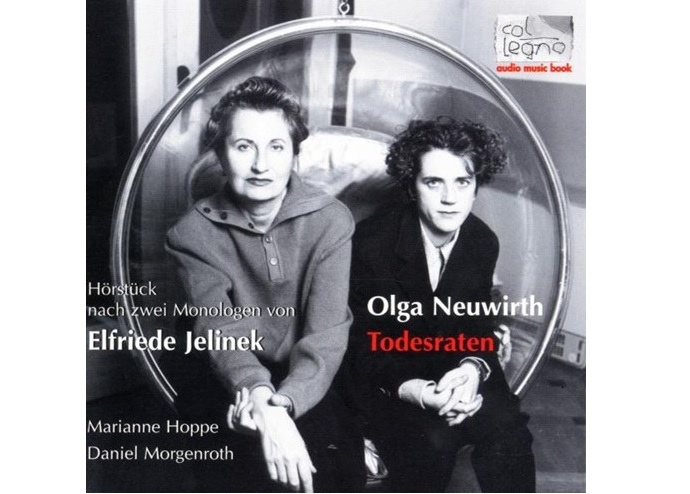

It is characteristic that this seemingly peripheral product from Olga Neuwirth’s workshop is aimed just as much as everything else toward the centre of her oeuvre – and this centre fans out like light emerging from a prism. Naturally, there is also an important streak of resistance running through her manifold artistic activities: it expresses itself not least in political form and can be heard as an echo of Bartleby. Neuwirth would prefer not, for example, to make music intended solely to relax or sound prettily mawkish. That kind of passive attitude disappointed her even in childhood when, the daughter of the Graz jazz pianist Harald Neuwirth, she would sit listening spellbound under her father’s piano, or later when she attended many concerts with her parents, still feeling a lack of deeper engagement with music in her family home. Which may well be why Neuwirth practises her métier today from so many different angles. She would, it seems, prefer not to confine herself purely to composition. Her material comes from language and sound, film and music, word, image and even space, from installation and performance, from comics, pop or science – certainly encouraged by her early encounter with the writer Elfriede Jelinek, which has also developed into a lifelong friendship plus artistic collaboration. And it may also reflect the great caesura in her early biography, which compelled her to seek out new paths. “As a punk in provincial Austria in the 1980s, it was the mean streets of the big city that attracted me more than the Alpine meadows, which is why I learned drums and trumpet,” she says. “I grew up with jazz and was even lucky enough to hear Miles Davis live... jazz was something liberating for me.” But at the age of 15 her dream of “becoming a female Miles Davis” was abruptly crushed – by a serious accident that resulted in injuries including a shattered jaw. It was in the midst of this major health crisis during puberty that a youth music workshop in the Styrian town of Deutschlandberg led by Hans Werner Henze provided the decisive impulse. It may be that Henze was more interested in the social than the artistic aspects of the project, but for Neuwirth it opened up a whole new world. “Perhaps I could finally be alone with my imaginings, I could write my way out of reality with codified microcalligraphies...”

Deutschlandsberg was also where she met Jelinek; their collaborations began in 1990. However, as fascinating as these works and projects with the future Nobel laureate may have been, at the time they nevertheless met with widespread indolence, incomprehension and sometimes blunt rejection from patrons. Over and over again in such situations it become apparent there is something else that Neuwirth would prefer not to: simply accept and tolerate disappointments and setbacks, or let representatives of any kind of power prescribe or silence her. And because she pushed back against arbitrary stage production decisions, going public if she felt her own clear visual ideas were being marginalised and overruled, she gained a reputation as a difficult woman. Despite her multiple collaborations, she remains shrouded in the aura of the loner – albeit a loner who is sought-after worldwide. That much is clear from the commissions she receives from institutions including Carnegie Hall, the Lucerne Festival and the Salzburg Festival and her performances with the most prestigious conductors, soloists, ensembles and orchestras, of which Pierre Boulez and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra shall serve here as just two examples. This wide-ranging concert devoted to Olga Neuwirth in Suntory Hall now completes a major gap for the Japanese public in the reception of a composer who, despite her extensive studies in Graz, San Francisco, Vienna and Paris in subjects ranging from composition and electro-acoustics to painting and film, says: “Essentially I’m an autodidact.” Since 2021 she has embodied and taught this independence as a professor for composition at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna.

col legno: WWE 1CD 20033 (Out-of-print)

Nonetheless, Olga Neuwirth’s work feeds off more than mere refusal – because hers is an art not of forgetting but of remembering. This can be seen in her many-faceted interest in history and in her own musical past. The fact she has created an operatic adaptation of and sequel to Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando with the French-American author Catherine Filloux is symptomatic: again and again in Neuwirth’s choice of themes, she shows an attraction towards outsider figures who, even if they have become stars, retain their vulnerability and maybe even perish as a result of it. Klaus Nomi, the pop countertenor pioneer who died of Aids in 1983, another musical hero of her youth, is one example, as is, for that matter, the long underestimated, misunderstood Herman Melville.

Queer, angry, delicate, confusing: Neuwirth’s Orlando was deliberately situated between a rock and a hard place. Virginia Woolf’s novel (1928) about a centuries-old artistic figure who begins their existence as a man, later becomes a woman, experiencing themself as one and the same person and perceiving the gender roles demanded by society as an intolerable restriction, is seen – at least in part – as a love letter by the author to her fellow writer and friend Vita Sackville-West. And to a certain extent, naturally, Olga Neuwirth too is reflected in Orlando. Above all, this “fictional musical biography in 19 scenes”, as the subtitle calls it, is enriched with a wealth of ideas and a flood of details that define Neuwirth’s musical cosmos. Everything can be found in it: historical music quotations from the Renaissance to the contemporary, as if dug out, battered and crumpled, from a heap of musicological bric-à-brac. Sound symbols from then and now, from the harpsichord to the pop band with electric guitars and drumkit. Ironically summoned noises from the silent cinema, which also recall the “mickey-mousing” animation technique. And live electronics effects – plus much more besides that Neuwirth uses to musically interpret the text down to the tiniest microelement. It is no coincidence that the composer describes her work as an “art in-between”. Ensemble, choirs and orchestra (the second violins are tuned down by six tenths of a semitone!), all dauntlessly took on this enormous challenge at the premiere on 8 December 2019 at the Vienna State Opera under the eternally confident, clear direction of Matthias Pintscher – and won. Orlando was chosen as premiere of the year in the international critics’ survey by the opera magazine “Opernwelt”.

▼Video: Opera Orlando (excerpt) World Premiere at the Vienna State Opera

In every respect, Orlando is a hybrid – between theatre and opera, between epic and drama, between postmodern and avant-garde, between the most diverse vocal and musical styles. The work itself, like its protagonist, thus defies all current categories, actualising its queerness on all levels. Something that is also certain to be achieved by Orlando’s World, the new orchestral suite derived from the opera, written in 2023 for a commission from Suntory Hall and premiered here with the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra conducted by Matthias Pintscher.

As in the other works being presented, this is not least an example of the composer’s habit, practised since her youth, of “writing her way out of reality”. And there is one more thing Olga Neuwirth would prefer not to: lecture the audience. Instead, she wants to “communicate, through music, notions of the painful and the delicate that resides around the world, the publicly ambivalent and humanly transient that surrounds it.”

Reference:

“As a punk in provincial Austria […] codified microcalligraphies...”: Interview „Ich war eine Punkerin“. Die Presse, April 22, 2016

“Essentially I’m an autodidact”: Die Presse – Spectrum, October 28, 2000 – as cited on Olga Neuwirth’s official site

“communicate, through music […] humanly transient that surrounds it”: Olga Neuwirth, “Music and Peace” (1998)

Walter Weidringer

(English Translation: Paul Richards)

Walter Weidringer lives in Vienna as a musicologist, freelance music journalist, critic (Die Presse, Opernwelt, crescendo) and broadcaster (Ö1, BR-Klassik).

■Video Opera Orlando (excerpt) World Premiere at the Vienna State Opera